Britain called and we answered

Real-life stories of the Caribbean diaspora.

Henry

Henry was born in 'Snell Hall' village in St Vincent, Grenada. The village was named after slave owner William Snell. 1720-1779.

On June 15th, 1961, Henry took the boat to England. His mum was so upset that her boy was leaving, that she couldn't bare to look when he got on the bus to take him to the port.

Just a few days after arriving, Henry was working as a carpenter for Wandsworth Council. He'd also found somewhere to live in Shepherd's Bush, so he sent for his wife, Marge, to come over from back home in Grenada.

One of Henry's first jobs was doing the 'shuttering' for the Winstanley Estate in Battersea, which was under construction at the time. Henry's job was to build wooden moulds that concrete was poured into to create the walls of the tower blocks.

Henry and Marge had four children together. When she was in her forties, Marge visited her sister in America. After returning, she was at the market when she had a stroke and died. Henry told me that Marge had always suffered from headaches. "My wife was so good that she died early. It's only the good that die young."

Henry is 94 now, and his eldest child is a pensioner. He walks without a stick and always sits on the top floor of the bus. He said, "When people get to my age, they get aches and pains but lucky for me, I don't have any."

Henry doesn't take any medication and never visits the doctor. "I'm happy in my own way, and I don't worry about nothing. The trouble with people is they all want to be rich. All you should want in life is to see the daybreak - that's all you need."

"I had my little job, I worked for Wandsworth Council until I retired - I still get my pension money from the government - what's better than that?"

"Every day, I'm up at 6am. I get a cup of tea and get out of the house. All I want is to keep going."

Henry told me he was in Clapham because he’d been doing a carpentry job. He always keeps his leather holdall in a Sainsbury's bag. "Because if people see you with a leather briefcase, they will want to steal it."

He told me that even though Marge died 47 years ago, he still has conversations with her in his sleep. Last week, she said, "Have you made up your arrangements for your funeral yet." Henry told me that he replied, "I ain't going nowhere."

"I was born in the gutter, and I lay in the gutter smiling, waiting for the water to take me to the big sea."

Despite being in his 90s, Henry always sits on the top floor of the bus.

Princess AKA ‘Blossom’

Princess Aldridge, AKA Blossom, was born in Trelawny in the Jamaican countryside in 1933

Her dad grew yams, bananas, cocoa, 'dasheen' (Taro plant), and another root vegetable, 'tyre'.

Her parents had children from previous partners, so Blossom had a big family with many siblings and step-siblings.

One of her earliest memories is being around four and starting at 'Quatty School', where you pay the teacher a penny-halfpenny weekly for lessons. (Quatty comes from the fact that a penny-halfpenny is a quarter of a Sixpence)

Her parents sent her there to get her education going before proper school started at seven years old.

She walked to school on rough stone roads; there was no tarmac back then. She enjoyed school, and just one teacher taught everything from arithmetic to gardening.

Around the time she finished school, her mum suddenly passed away. She had previously hit her head, which affected her blood pressure, and she died sometime after the accident.

At the time, this never really sunk in for Blossom - she thought her mum had just gone away to another country. There was no such thing as an undertaker - you died on one day and were buried the next. It was all so sudden that it didn't feel real to the 16-year-old.

At her first job, she learnt embroidery. She could hand sew and use the machine but couldn't get into dressmaking. She left this job and went to Kingston to work as a domestic for a couple from the Cayman Islands, looking after their new baby.

One of Blossom's most vivid memories of Kingston is sneaking into the grounds of Kings House to see Princess Margaret, who was staying there while on a tour of the Caribbean. There was no security then, so Blossom and her friends crept under the fence and into the compound to get a better view.

When her employers decided to return to the Cayman Islands, they asked Blossom to accompany them. Blossom decided against this, so she had to find a new job.

She went to see one of her older brothers who lived in the district of St Thomas to the East of Jamaica. It was through her brother that she met Solomon, who was known as Mike (Many West Indian people have a nickname). She remembers that it was all down to eye contact - they knew immediately that they liked each other.

Mike was a shoemaker, and he had a room in a house near the church in a small community, and Blossom moved in with Mike.

Nobody had a problem with them living together before marriage, but Blossom needed to find work. A few kids were running around, and the pastor permitted her to set up a school in the church. It was sixpence a week, and she had about six kids in her class.

Mike saw the adverts in the Jamaican Gleaner encouraging young people to come to England. And in 1956, he decided to go.

Blossom was due to see him off at the dock but discovered her dad was gravely ill. She said goodbye to Mike and hitch-hiked back to her district on a market truck.

When she got to the hospital, her dad looked so sick that she barely recognised him. He was only 54. He'd had a hernia operation, and the surgeon had left a piece of equipment inside him. In those days, there wasn't a nurse that counted all the tools in and out, and this error caused him to get an infection. He died the following morning, but at least Blossom got to see him one last time.

Blossom continued teaching until Mike wrote, saying that he had a place to stay in London and had found her a job and that she should get a passport and come. In 1957 Blossom boarded The SS Venezuela for the UK.

Mike and his sister were waiting for her at Victoria Station, and luckily, they had a coat for her. It was March, and it was foggy. At 23, this was the first time in her life that Blossom had ever experienced feeling cold.

As they left the station, she looked around and wondered where all the houses were. She thought the houses were factories because of all the chimneys belching smoke from the coal fires. There are no chimneys in Jamaica. For a while, she even thought the chimneys were canons pointing at the sky.

Mike had rented a room at 3 Lammermoor Road in Balham from a West Indian landlord called Mr Robinson. It was just a room with a paraffin heater. There was no carpet, just Lino on the floor.

You had to put a coin in the meter for electricity, and if you wanted a bath or a shower, you had to go to Tooting Baths, where you were only allowed 15 minutes. This was a surprise to Blossom. The adverts about England said the streets were paved with gold, and she wasn't expecting to live in such conditions. Back in Jamaica, Blossom's house was spacious and had its own bathroom. Despite this, being in London and seeing Mike again after their year apart was exciting.

The next day Blossom and Mike took the 155 bus to Colliers Wood to the factory where Mike was already working. The factory worked in metal and made rough components for items like toasters or irons. Once the parts were made, they were sent to another factory for finishing and then would go to another to be made into the final items.

Blossom worked on all sorts of things on the production line and, most of the time had no idea what she was making. She remembers having to weld a small bowl onto a metal plate. Years later, back in Jamaica, she went to church and saw a communion bowl welded into the middle of a plate. It was only upon seeing it all polished up that she finally realised what she had been making all those years before.

It was very hot in the factory, and Blossom had to wear leather gloves to protect her hands against the sharp, rough metal. She worked in the women's section on smaller items, whereas Mike worked in the men's area on larger and heavier products.

During this time, Blossom made a lot of friends. This was before they had children, so the couple often went out. They loved the cinema, and Blossom remembers watching ‘Ben-Hur' at the Classic Cinema in Balham. They paid a shilling to get in.

In 1958 the couple married in Ramsden Road Baptist Church.

They wanted to start a family, but Blossom said that there was no way that she was having babies in a single room, so they looked for flats in the Local paper.

A Self-contained flat was going for £2.50 per week in Louseiville Road, Balham. A Polish couple owned it. Blossom was very well-spoken on the telephone, and she called her potential landlady. They had a pleasant chat and arranged to view the flat that afternoon.

As soon as Blossom got there, the landlady took one look at her and said the flat was gone. Blossom looked her in the eye and said, 'It's not gone; it's because I'm coloured' (In those days, it was common practice to use the now offensive term coloured). The woman had no answer for Blossom; she just shut the door, and Blossom and Mike had to find somewhere else to live.

The same thing happened not long after when Blossom phoned up about a job. She was virtually offered the job after talking on the telephone, but when the boss saw her in the flesh, he said the job had gone.

Eventually, the couple found somewhere to live. By then, Blossom worked as an orderly at The Fountain Hospital in Tooting. (Now the huge St George's teaching hospital). Mike was working as a carpenter, making furniture in a factory where he continued to work until he retired. He also did the sound systems at "House to House" parties which bought in a little extra cash. Blossom would always go to the parties, "It was nice, people you know. It was soft music. No fighting, no knives, everyone dressed up smart."

In 1961 Blossom had her first baby, a boy called Ken, at the Weir Maternity Hospital in Balham (Now a Travis Perkins). She shared a bathroom with two white girls who were also heavily pregnant.

Whenever Blossom had a bath, the pair kept coming into the bathroom to try and look at Blossom's behind to see if she had a tail. In those days, some white people thought that black people had tails. Blossom, who doesn't take nonsense from anyone, wasted no time showing them otherwise by waving her behind in their faces.

Blossom and Mike then had two daughters, Yvonne and Carol.

During this time, Blossom worked nights as an auxiliary nurse. She worked in the geriatric ward, writing reports on the patients - how they slept, if they'd taken any medication, etc. When she got home from work in the morning, Mike, who had been watching the kids, would be getting ready for work.

By then, the landlord said the babies were making too much noise, so she applied for a mortgage from Nationwide, and they got a deposit together using the Pardner scheme. The Pardner scheme originated in Jamaica and involves a group of friends or relatives putting money into a shared pot to pay for large items like cars or house deposits.

The house they bought was in Letchworth Street, Tooting.

Meanwhile, the matron at the hospital was impressed with Blossom's work. She encouraged her to go beyond being an auxiliary and applied to the School of Nursing on Blossom's behalf.

Of the five women who applied then, Blossom was the only one who passed the test. She became a student nurse in 1972

Once she qualified in 1974, Blossom was one of the first nurses to work at the newly opened Charing Cross Hospital in Hammersmith. She worked there until her retirement in 1993.

Blossom was still experiencing racism in the hospital environment.

She remembers getting the bus to work at the hospital. A white woman was sitting next to her. She asked all the other passengers around her if she was going the right way to the hospital. She refused to talk to or even acknowledge Blossom.

Not long after Blossom got to work, the same woman arrived. She was visiting her husband, who Blossom happened to be caring for. The woman recognised Blossom immediately, and there was an awkward silence before Blossom said, "If you'd just spoken to me on the bus, I could have taken you straight to him."

On another occasion, a patient from South Africa was at the hospital. This was during apartheid, and the woman was extremely rude to Blossom.

Blossom noted that during the woman's operation, the nurses, the porter and the doctors who cared for her were all black.

When she came around from the anaesthetic, Blossom said to the woman, "See, we didn't kill you. We helped you." Blossom was pleased to see that the woman's attitude changed after this experience.

In Blossom's words regarding racism, "We tolerate it. I didn't pay them any mind. We meet hell, but things will get better one day at a time."

In 1981 after 20 years of marriage. Blossom and Mark divorced.

Blossom continued to work as a nurse, and some years later, she married Roy. He was also from Jamaica and, like Mike, was also a carpenter. She knew him from the house parties back when she was young. By then, Blossom was in her 50s.

After retiring, the couple decided to move back to Jamaica. It was Roy's idea to go back; he had had enough of the cold British weather. Blossom had lived in London for 41 years. Being married to Roy felt like a new start, and she was happy to return.

They already owned a piece of land Blossom had bought with her brother and built themselves a new house.

Britain is no longer as racist as it was, but preconceptions remain. Blossom invited an English friend over to her new house for a holiday. Her friend admitted that she thought Blossom's house would be a small shack surrounded by dirt and was surprised to see a large home with plenty of space and beautiful gardens.

Blossom is now 91 Her first husband, Mike, and her second husband, Roy, have since passed away, and Blossom lives alone.

Blossom must be careful in Jamaica because, having come from the UK, the locals assume she has a lot of money and try to charge her more at the shops if they hear her London accent.

All those years ago, when she was looking for a flat or trying to get a job, people made assumptions about her based on her accent. Ironically, something similar happens to her now when she goes shopping in Jamaica.

Despite this small inconvenience, Blossom loves living in Jamaica. "I'm glad I came to England, but I'm also glad I returned home."

Janet

Janet was born in 1935 in 'Kitty', a neighbourhood of Georgetown, Guyana.

Her dad owned some land as well as the village shop.

Janet did well at school. She was also sporty and loved tennis, athletics and cycling.

She went on to work for a printing company called 'B.G. Lithographic", where she did print finishing and putting together leaflets and booklets.

The company had a sports team where Janet regularly competed in track and field events and often won medals.

An accident damaged her knee, so she could no longer compete. Janet came to England on the SS Ascania in 1961. Janet’s older sister, known as 'Baby', was already in London and working as a machinist. She had a job and somewhere to stay lined up for Janet.

SS Ascania

Janet was told that the streets of 'The Motherland' were paved in gold. She was disappointed when she arrived on a freezing cold smoggy day. She wasn't expecting to see so much poverty in England either. Her parents had a nice house and land, and back in Guyana, the thought of paying to keep warm was unthinkable.

Despite this, being in her early twenties, Janet loved the excitement of living in London. She has always been into music and, in those early days, often attended house parties. It was a lot of fun, and she made many friends.

She then got work as a nurse at St Ebba's Hospital in Epsom, which was a hospital for the mentally ill. It was around this time that she met John. He was from Nigeria and was a trained mechanic living in Tooting. The pair married and had their honeymoon in Paris. The couple had 3 daughters and a son.

John went on to become a bus driver,

When the kids were small, Janet stayed at home. She would often take them on day trips to museums and the zoo. She encouraged them to share her love of sports. Several cups and medals won by her kids are displayed at her house.

Janet used to love going to Wimbledon to watch tennis. (Her daughter was one of the first black ball girls at Wimbledon).

The couple on holiday in Mexico.

Once the kids got older, Janet returned to work and got a job at M&S. Firstly in the womenswear department and then in the food hall. Before going to work, she always left little snacks out for the kids so they had something nice to come home to when they returned from school.

Her first pay packet at M&S coincided with the opening of McDonald's in Croydon. This was one of the first in the country, and she remembers how novel and exciting it was for her and the kids to visit this strange American store.

Back then, shops were all closed on Sundays, so on a Saturday afternoon, the staff at the M&S got to buy all the unsold food at a big discount, so Janet was able to buy lots of treats for her family.

Janet retired after 21 years at M&S and has lived in the same SW London house for nearly 40. Her estate once had a pub frequented by the National Front, and there were a lot of racists in the area. Janet remembers back in the 80s, her neighbours opening their windows and playing recordings of the racist comedian Jim Davidson at full volume.

Janet never took the racists that seriously. She never understood how they could look down on her when they all had dead-end jobs and lived in virtual poverty. Janet was well-educated from a good family and had come to England as a young woman purely because it was an exciting opportunity for a girl in her twenties. Not because she had to come to earn money. The area is much more cosmopolitan now, and attitudes are thankfully changing in Britain now.

Janet used to love knitting, but arthritis has put a stop to that. She still loves watching sports and always looks forward to seeing athletics and tennis on TV.

Janet is now 88. She has vascular dementia and is cared for by her daughters, Pearl and Beverley. Pearl was a huge help with this interview.

Janet may struggle to remember everything, but she still has her sense of humour. "When I first came to England, All I used to do was go to house parties. Nowadays, all I seem to do is go to funerals.”

Janet’s caught Pearl was a huge help with this interview

agnes

Agnes with her ‘Great-grans’

Agnes longed to see her big brother George again. He'd left Guyana for the UK when she was 11. So in 1959, when Agnes was 19, she boarded the SS Venezuela and set sail for England.

Agnes remembers the boat was filled with people from all over the West Indies, Jamaicans, Barbadians, St Lucians, amongst others. Some were going to meet their parents, their partners or other relatives. Some were going to study and some to work.

Agnes enjoyed the journey; she was a friendly and sociable 19-year-old and exchanged many backstories with those she met while crossing the Atlantic. She shared a cabin with a girl her age, Velma, from Guyana. Velma was to become her best friend, and they remained so for over 60 years until Velma recently passed away.

When she arrived in London, her brother George was waiting for her at Victoria Station. Although she had not seen him for eight years, she recognised him immediately.

George, his wife, and their children would share their home in Balham with Agnes for 11 years.

Within a week of arriving in England, Agnes was escorted by her Sister-In-Law to the Labour Exchange in pursuit of a job.

Agnes's first job was in a laundry operating the steamer. This did not last long, as she was terrified of the huge machinery.

Her next role was in a factory, assembling parts, for things, like irons and toasters. While working at the factory, she made another of her lifelong best friends, Lucille, aka 'Miss Lou'. Now deceased.

Agnes then wrote a job speculative letter to The Fountain Hospital. A small hospital for children with mental disorders. She secured a position as a Nurse. The Fountain Hospital went on to become the huge St George's Teaching Hospital that dominates Tooting today.

After a few years, Agnes took her nursing skills to St James' Hospital in Balham, where she worked in an operating theatre.

At first, she found seeing the operations hard to take, "It was a bit frightening, but eventually I got used to it."

During the '60s, West Indian immigrants would host parties in one another's houses. It was at a house party that Agnes met her husband, Marvin. A qualified teacher from Guyana, who, owing to the discrimination in England at the time, could only secure building work.

Unbeknownst to Agnes, Marvin had noticed her back in Guyana while she was out with friends. He had liked her immediately and could even recall the pink dress she had been wearing, but he didn't make his feelings known at the time, as she was only 17.

Now she was older, and they were in London, Marvin wasted no time getting to know her. They courted for a while and later married at Wandsworth Town Hall. She and Marvin had a good marriage and went on to have four children.

Agnes continued to work, and as the children grew, she qualified as a Residential Social Worker.

This was a challenging job, but she met lots of interesting people. An old resident, an Irish lady, told her something she never forgot while discussing their children, "When your kids are small, they wear out your hands, and when they are big, they wear out your heart".

In 2020 during the pandemic, Marvin passed away. They'd been happily married for 60 years. Agnes misses him every day but is philosophical. "He's gone on ahead of me." Agnes keeps Marvin's photo beside her favourite chair in her South London home. She often looks at the picture while listening to her favourite radio station, Smooth Fm.

Agnes loves her family. She now has "Grans" and "Great-grans" To them, she is simply "Nan". This shot of Agnes and her great-grandchildren was taken on her 83rd birthday when her whole family came together to celebrate with her.

Agnes has no regrets about making the journey from Guyana to Britain. "You meet up with good, you meet up with the bad, you meet up with indifference. It's down to you to make your own life."

(Thanks to Agnes's daughter Claudette for her help with this interview)

Agnes with her ‘grans’

Monica

Monica often gets the bus to Trafalgar Square to sit on her favourite bench. She loves the square because there is always something going on. It also gives her a chance to do her scratch cards.

Monica is 77 and was born in St Lucia. In 1960 when she was 18, she came to the UK on the ship 'Bianca C.' Monica was seasick for most of the 3-week voyage. It could have been worse, because a year later, the ship sank off the coast of Grenada.

Life wasn't easy when she first arrived in the UK. She saw the signs in the windows, “No blacks, no Irish and no dogs" and the chilblains were horrible.

She got a civil service job and, eventually, became the Prime Ministers messenger in Number 10 Downing Street.

She worked for Tory PM, John Major and Labour PM, Tony Blair. She said they were always nice to her, "Because I was always nice to them."

Tony Blair introduced her to Mandela. She remembers waiting in the hallway, and before she even saw him, she immediately recognised 'Papa Mandelas' voice. He signed her book for her.

There was a lunch at Number 10 to celebrate ex-PM Ted Heaths' 80th birthday. Mr. Major asked Monica if she would like to meet 'Her Majesty,' and Monica was introduced to The Queen.

Monica told me that the Queen was softly spoken and asked, 'How long have you been here?' Monica wasn't sure if she meant how long you have been in the job or how long you have been in the UK. She can't remember her answer because she was so nervous - she just curtseyed as the Queen replied, "I hope you enjoy your stay."

She said the rudest visitor was Vladimir Putin. He walked past her. He said, 'Goodbye,' but didn't look at her once.

Monica met many famous people like Shirley Bassey and Cliff Richard, and she enjoyed the parties on the lawn at the back of Number 10. She said there was no Covid then, so the parties were no problem.

Monica has two sons and 5 grandkids and owns her house in East Ham.

When she was at school back in St Lucia. The girls hoping to come to the UK had to write down what they wanted to achieve when they got here. Monica wrote that she would love to meet the Queen. The teacher laughed and said, 'You never will.'

ESTher

Esther is originally from the Caribbean and now lives in London where she works as a performing artist.

As you can see, Esther also loves fashion.

Arnold Ebenezer Tomlinson

Arnold Ebenezer Tomlinson was born in the parish of Westmoreland, Jamaica in 1923. He grew up on a farm with his 7 brothers and sisters. His dad grew sugar cane and kept donkeys; Arnold would help on the farm after school.

He came to England in 1956. He remembers being shocked at how cold it was on the dock as he disembarked at Southampton. He got lodgings in Battersea and a job working at a nearby factory. Once he got settled, he sent for his wife. Arnold did many jobs back then, including working in the canteen at London Airport (Now Heathrow). He used to peel the potatoes and mash them up. However, he spent most of his working life as a painter and decorator for Southwark Council.

When he wasn't working, Arnold enjoyed going to house parties. He never really went to the pubs because he wasn't much of a drinker. "I'm not a pub man. I liked to go dancing."

The couple had a son and saved enough to buy a house in Stockwell. Arnold was the first Tomlinson to come from Jamaica to England. He led the way for other family members. He took in his nephew, who came to England after his father died. He also helped his two brothers get established in London. Arnold has outlived them all.

Arnold and his wife divorced in 1979. In 2000, a friend introduced him to his new wife, Mervelee. They married at the Peckham Registry office and now live in Bermondsey.

Arnold always loved gardening. He'd make the front garden look pretty with flowers and grow vegetables at the back. It's too much for him now, so Mervelee has taken over the task. He also loves a flutter on the horses. He used to go to the bookies himself, but now when there's a big race or fight, Mervelee places the bets for him. Every day, Arnold makes breakfast. He does toast and tea and boils eggs. He no longer eats the eggs himself but cooks them for Mervelee.

Despite being 100 in just a few weeks, Arnold has perfect vision. He doesn't even need reading glasses to read his daily paper which he reads from cover to cover while drinking Baldwins Sarsaparilla (A soft drink).

Looking back at his 65 years of living in England. Arnold thinks the country has treated him 'good and bad.' But when he weighs it all up, he feels that the good outweighs the bad.

Thelma

Thelma was born in St Andrew, Barbados in 1932.

She had 5 brothers and two sisters. Her mum died in childbirth when she was just 8. Back then, people didn't know much about contraception, and Thelma thinks that giving birth to all those babies eventually became too much for her mother.

Thelma was a bright girl and did well at school. Once she got her shorthand and typewriting certificates, she went on to do secretarial work within the Civil Service in Barbados, but the posts were only temporary.

She'd always been told that the streets of England were 'paved with gold' and that 'The motherland' was a place of opportunity. So when she heard that the UK Government was recruiting people to work on the buses, instead of waiting to get a permanent post in Barbados, she decided to join up.

So in 1956, aged 23, Thelma got the ship from Bridgetown to Southampton (11 days) and then a coach up to London.

Thelma was disappointed when she first arrived in the UK. It was freezing cold, and the place where she had to stay was awful.

She remembers seeing the signs in the windows, "No blacks, no Irish, no dogs." Some people, even those in the church that she attended, were rude because of the colour of her skin. It certainly wasn't the warm welcome she was told she would get.

She managed to get a job straight away as a conductor on the bus.

Running up and down the stairs with the ticket machine strapped to her was hard work. The bag she wore to carry all the coins became heavy as the day progressed, and she was exhausted by the end of her shift.

Sometimes, passengers would drop their coins on the floor when paying their fare rather than risk touching a black person's hand.

Thelma's stint on the buses was short-lived because she then got secretarial work for the government at Millbank in Westminster.

She enjoyed being a civil servant because once in the organisation, you could move around and work in many different departments, so the job was always interesting.

Thelma went on to spend nearly 30 years working for the Service. She took voluntary redundancy during the recession of the late 80s. She did temp work until she got her pension when she was 60.

Despite many obstacles, Thelma has done well in England. She bought her house and raised her kids, and is also a grandmother.

Her husband passed away 17 years ago. She still misses him, but in Thelma's words, 'What can you do?'

Thelma says it's not easy being 91 in modern Britain. Everything is online nowadays, and many shops have stopped taking cash. The high street banks are all closing their branches, which is a real problem for older people. Those bank adverts on TV saying, "We are by your side," always make Thelma laugh.

Thelma would find it difficult to live in Barbados now as the heat makes her feet swell up, but she enjoys visiting from time to time.

Despite its shortcomings, London is where her family is, so London is her home.

Philip

Phillip is originally from British Dominica and was a trained carpenter. He told me, "I can take a piece of a tree and turn it into a cabinet."

When he was young, many of his friends left British Dominica for America as soon as possible. Phillip stayed because his work was 'going good' and he had 'plenty girlfriends.' However, when he was 24, he got one of them pregnant. As soon as he discovered this, he found his passport and got on the first boat to England.

Phillip sent money back home to help pay for his daughter's upbringing but stopped when he found out that the money was being spent on other things, and he lost all contact with her.

In the 70's he was playing darts in a local pub when a woman turned up and started talking about his past. Phillip didn't understand how this woman knew so much about his life until she told him that she was his daughter. Phillip told me, 'It was lucky I had strong legs because I nearly fainted when I realised who it was - she looked like my sister.'

Phillip's daughter lived in America and had come to the UK to search for Phillip. She had a rough idea of where he lived and had heard that he was into darts, so was going into different South London pubs hoping to find him. Eventually, she hit the bulls-eye and found her dad. After this meeting, they saw each other every day until she returned to America, where she still lives as a retired accountant. Despite the distance between them, Phillip and his daughter have remained close, and she calls him every Sunday to check that he's okay.

Phillip no longer plays darts as he damaged his shoulder when he was the victim of a racist attack in Brixton in the '80s. Phillip told me that it was lucky there was thick snow on the ground as it cushioned his skull as the attacker repeatedly banged it against the pavement. Phillip was saved by a passer-by, a guy from Malta who dragged the man off of him. A few years ago, Phillip bumped into the Maltese guy and got the chance to thank him for saving his life.

I took this shot on the first day of Lockdown Two. Phillip said he's refusing to stay indoors as he did during the first lockdown as his body 'locked up' from lack of activity. This time the 91-year old told me that he will continue his daily routine of Walking on Clapham Common no matter what.

Phillip and his daughter when they we reunited.

Stella

Stella has a great sense of humour. As I attempted to take her photo, she said, "Take your time and hurry up." She then told me in a whisper, "I'm 89 but don't tell anybody."

Stella came to England from Guyana in 1955. She enjoyed the journey across the Atlantic. It took 2 weeks, and every night, they would show movies in the lounge. On board the ship were families, single men and women and many children. Everyone was excited about starting a new life in England.

Her husband, Cecil, had already come to England. He was working as a carpenter and living in Tooting. Stella left their son with his parents until she got settled.

Stella wasn't sure about England at first but it was her sense of humour that helped get her through those early years. A white woman once looked at her hands and said, "Oh, look at that, you wear a wedding ring just like us". Stella replied, "We normally wear our rings through our noses but put them on our fingers before we get off the banana boat."

Stella and Cecil lived in a single room in Tooting. Cecil worked, and Stella trained to become a nurse. The couple also had a baby daughter called Wendy

Stella then sent for her son, but her in-laws had grown attached to him and wouldn't let him come. Stella joked that although many English people think that people in the Caribbean lived in mud huts, her in-laws had a big house with 6 bedrooms. They argued that there was no way that they were going to send their grandson to live in a single room in South London. So Stella's son remained in Guyana with his grandparents and still lives there.

Once Stella passed her nursing exams, she worked in the infectious disease ward at St Georges Hospital in Tooting.

She said that the hospital had a strict hygiene policy. You'd scrub your hands, go into the ward, put on overalls, and then scrub your hands again. There were no disposable surgical gloves in those days. She said you had to go through the same process on the way out. She said that all the hand scrubbing made her hands sore.

The nurses were given castor oil cream to soothe their hands, but it had a strong smell that Stella was self-conscious about on the bus ride home. The whole time Stella was a nurse, there was never any cross-infection.

Stella's daughter Wendy became a teacher. When she was in her early fifties, she started to get stomach pains. Because she was so dedicated to her work, she wouldn't visit a doctor until the school holidays. When she finally went, it turned out that she had advanced liver cancer, and sadly, she passed away shortly after.

Wendy had five children who often visit Stella. Stella feels blessed that she has all her grandkids around her. She says when they leave the house after a visit, 'The silence is deafening.'

Cecil passed away in 2009. He loved gardening. He'd grow vegetables in the back garden and flowers in the front. Stella told me everyone was friendly on the road where she lived in Tooting. Back then, people were always popping in and out of each other's houses. Everyone grew vegetables and cared for their gardens. The neighbours would share plants and seeds.

During this time, Cecil planted two beautiful roses in the front garden. Now that she lives alone, Stella got the garden paved because it was too much for her to look after. She ensured that the builders left Cecil's roses untouched. Every summer, without fail, they always burst into bloom.

Stella at her recent 90th birthday.

Max

For as long as he can remember, Max has always wanted to play music.

Max was born in Trinidad in 1929 and was one of 12 kids. His dad was a headmaster, and his mum was a teacher. They lived in a large house in the capital, Port of Spain. Neither of Max's parents were in the slightest bit musical. They, like the majority of Max's siblings, were academic people. The house had a piano, and one of Max's earliest memories is reaching up to 'tinkle away' on the keys trying to make tunes. Max could play by ear. If he heard a piece of music, he could work out how to replicate it on the piano. He didn't just love the piano. He tried every instrument he could lay his hands on, including the cornet, saxophone, and clarinet. He even had a few violin lessons.

As soon as he left school, he started a band, The Max Cherrie Quintet, where Max played the piano. The band did well and got work at functions and at local clubs.

However, Max always wanted to travel and had intended to go to New York. However, while walking in the town, he saw the Italian passenger liner, 'Ascania', docked in the harbour. It was due to set sail for England, and Max, impatient to travel, decided to go to England first and then on to New York after.

He packed his bags and, just before he boarded, decided to take a steel drum with him. It was an impulse thing. He was a pianist and had never played the steel drum before, but he thought it might be a bit of a novelty. It was certainly a lot more portable than a piano.

When he arrived in the UK, he couldn't believe the vastness of London. It was June, so at least the weather wasn't too much of a shock for him. He got a room in Maida Vale with a friend who had already settled in London.

Max started looking around for work as a pianist. The artist, musician and impresario Boscoe Holder was taking a dance troupe to Geneva and wanted something different to accompany them. Max told him that he had a steel drum and got the job.

The only problem was that Max hadn't yet learnt to play the drum. He hadn't even touched it since boarding the boat back in Trinidad. He had just a week to learn before the group left for Geneva. Fortunately, Max's ability to play by ear meant he had no problem getting acquainted with this new instrument.

Once they'd arrived in Geneva, they played in a nightclub called Maxime's. The dance troupe were a mixture of people from Nigeria, Jamaica and Trinidad. It was like a little family, and Max had a great time. He loved Switzerland. It was a beautiful place, and the people were so friendly.

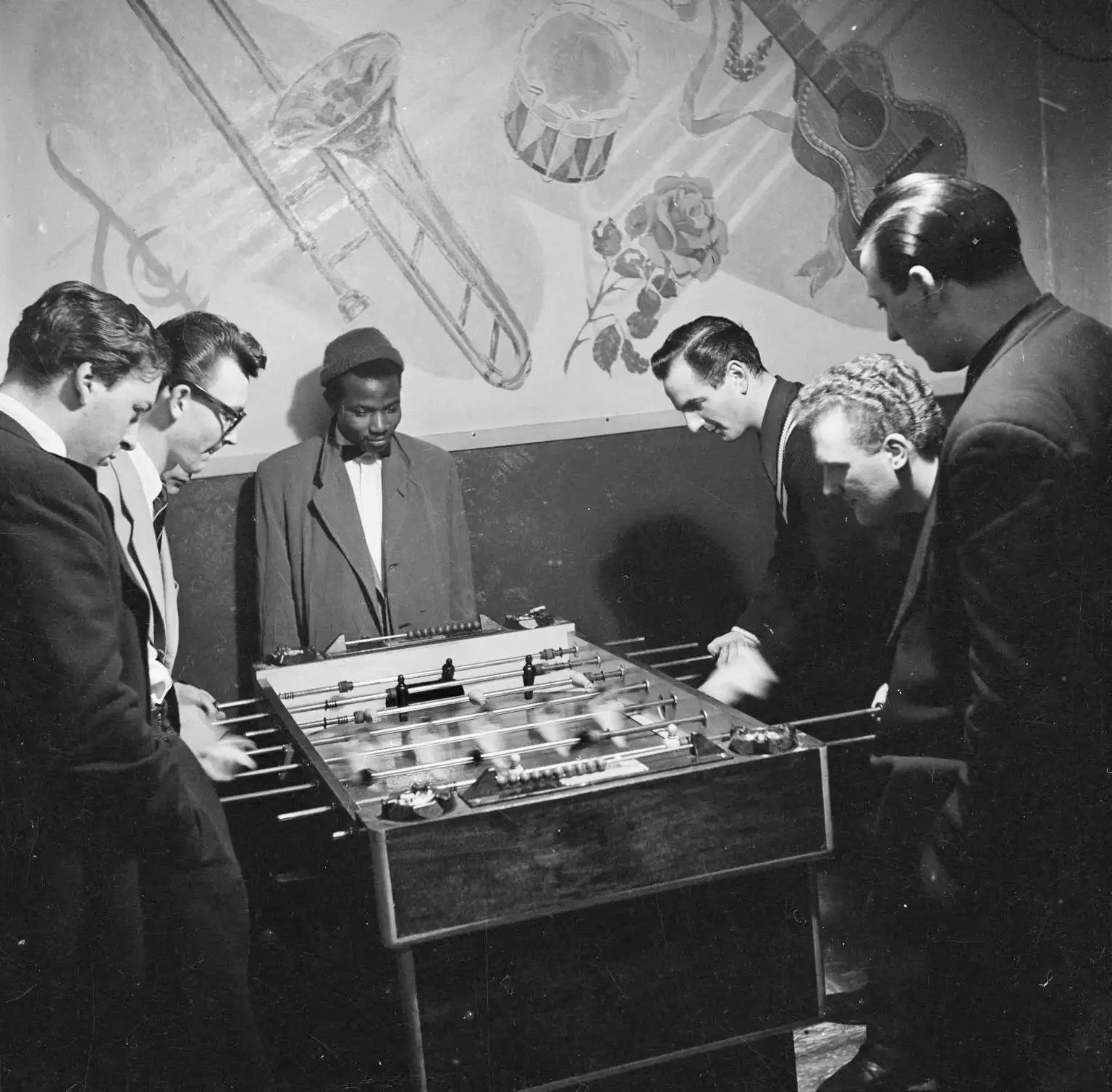

Once back in England, Max often found gigs by going to 'The Harmony Inn' cafe in Archer Street, Soho.

The Harmony Inn was an all-night greasy spoon frequented by everyone in the London music scene, along with several Soho gangsters. It was next door to the Musicians Union and where one would find out on the musical grapevine who was looking for a pianist, a drummer, a horn player etc.

All there musicians met up at Soho’s Harmony Inn

It was here that Max met up with Russel Henderson. He was a pianist and had come to London from Trinidad a year before. He told Max that there was a club in nearby Berwick Street called 'Heathers" that was looking for a pianist. It was run by a German woman (Heather), which was very unusual so soon after the war.

The clientele were mainly businessmen having a cocktail with their secretaries before they got the train home to their wives.

He enjoyed the work, and it was here that Max 'teamed up' with a German barmaid who worked at the club. She was a dancer. Towards the end of the war, the German high command sent dancers to Paris to try to keep up the soldiers' morale. When Paris was liberated, the Germans fled. Max's girlfriend stayed and hid with some French friends before eventually making her way to London.

By then, Max had moved in with his elder brother Ralph who also played the steel drum. He had just bought a house in Maida Vale. Houses back then were, according to Max, 'As cheap as chips.' His brother had only paid a couple of hundred pounds for a whole house, and he let Max live in the basement flat. Although wages were small back then, living was cheap. Coming from the West Indies meant that Max had the advantage of eating foods that English people didn't. He would go to the butchers and get things like pigs' tails and trotters for free. He would cook them Caribbean style, and they'd be delicious.

Max met up again with Russel Henderson. He was starting a steel band with Sterling Betancourt, and they needed a third member. Max agreed, and 'The Russ Henderson Trio' was formed. They travelled all over Britain playing the steel drums.

During this time, Max developed the technique of playing the drum with one hand and shaking maracas- or in Trinidadian parlance- 'shak-shak' with the other. This has since become a standard in the world of steel bands.

Things were going well, so Max got a small building society loan and following his brother's example, he bought his own house.

Around this time, Max met his future wife, Margaret. She was from Leicester and was one of the dancers that worked at one of the many venues where Max performed. Max and Margaret married in 1956 in Westbourne Grove and went on to have 2 kids, Paul and Maxine.

It wasn't long before Max decided to set up his own band, 'The Cherry Pickers.'

This was a good decision because this was at the height of the variety scene in Britain, so there was lots of work all over the country. The Cherry Pickers performed in shows alongside comedians like Frankie Howard, Spike Milligan and Harry Secombe. After the show, they'd all go drinking. Max said he'd never forget Spike Milligan having everyone in fits of laughter at one of the after-show parties. The upper classes also seemed to love the sound of the steel pan, and the trio did high-society events like hunt balls and debutante parties. At such events, Max met Princess Michael of Kent and Princess Margaret, both fans of steel bands.

As well as playing the steel drum, Max continued working as a pianist in nightclubs all over London. He also worked as a musician on P&O cruises in the '70s. Max has always loved to travel, so this was a great gig for him. It was also great for Margaret because performers were allowed to bring their partners, so she really enjoyed these cruise holidays.

When Max's son Paul grew up, he joined the band too. Paul still plays in the band and also works in artist management, looking after a wide range of performers.

When Max's daughter Maxine got into music college in Manchester. Max went to help her look for student digs. He didn't like the look of the places on offer, so he decided to buy a house for her to live in and rent out the other rooms to students. The one he bought was much nicer than the student digs and was only £25,000. Maxine is now a full-time music teacher but still performs in The Cherry Pickers.

Back in London, Max's marriage wasn't going so well, and he left the marital home. He moved to Manchester when a friend said he had an empty house that Max could rent for just £45 per week. Once the students had left the house he had bought, Max moved there, and he still lives in Manchester today.

Once they had parted, Max and his wife got on much better than when they were living together as a married couple. They often went on holiday together to places like Benidorm, Corfu, and Italy and remained good friends. Being Catholic, Max never considered divorce even though they were separated.

In 1998 Margaret was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. During this time, she and Max got much closer and had a big holiday planned in Trinidad. Sadly, the cancer was aggressive, and she passed away before they got to go.

For years Max had known a lady in Manchester named Val. Initially, It was never anything more than a friendship, but gradually they became romantically involved and married in 2003.

Val was 15 years younger than Max, who was in his 70s then. He often joked that Val would look after him when he got old. This wasn't to be because Val got Alzheimer's, and Max ended up looking after her. As the disease progressed, Val would get confused and sometimes walk out of the house and wander off. Max would follow her in the car to make sure she was safe and that she didn't get lost.

The couple had some great times together. They went on holiday all over Europe and Canada thanks to Max's love of travelling. She passed away in 2017.

Max is 92 now and lives in an assisted care apartment but is still very independent. He does his own cooking, shopping and cleaning, and he still loves to travel. After deciding not to go to New York over 70 years ago, he finally visited the city with his son Paul in 2014.

Arthritis has meant that Max now finds it very difficult to play the piano, but he still plays the drums. The Cherrie Pickers have been going for 50 years now, and Max still plays the drum with one hand and the 'Shak Shak' with his other.

Recently, Max has been travelling with Paul around Britain to schools where he gives talks about his eventful life as well as demonstrating his steel drum. He has also taken up singing in his daughter's choir. He really enjoys this new way of expressing himself musically.

One of the downsides of living so long is that you go to a lot of funerals. He's lost two wives and outlived all his brothers, sisters, and friends.

He says there's no particular secret to his longevity. He feels that there's no point in getting stressed about anything and never quarrels with anyone. He joked that his wives would quarrel with him, but he would never quarrel back.

He hasn't smoked for over 32 years. He gave up when he was 60. He likes pasta, rice, and spicy food but doesn't eat vegetables. He still enjoys a drink or two and always has 3 sugars in his coffee with full-fat milk.

He enjoys going to Trinidad on holiday but would never go back there to live. He's glad he decided to come to England over 70 years ago and has no regrets. He's also glad that he took that steel drum along with him. After all, it has shaped his and his whole family's life.

Veronica

Veronica came to England from Jamaica when she was 9. Her mum was just 25 and had given birth to Veronica when she was a teenager and still at school.

Everyone knew Veronica's mum as Pearl, and she was a talented seamstress. Veronica's dad, Charlie, worked for British Rail. He was also a skilled carpenter and picture framer and could make and repair shoes as a hobby. They settled in Clapham in SW London.

For newly arrived West Indian families, inherent racism from the banks and the fact that they had no history in England meant that getting a bank account was very difficult. Because of this, many people from the Caribbean set up 'Pardner' Schemes.

The Pardner system was initially brought to Jamaica by enslaved Africans and used to purchase freedom.

The scheme is based around a group of friends, neighbours or relatives agreeing to contribute money into the pot each week over a fixed term. Each month, a member of the scheme gets the whole pot which means they get a lump sum to help pay for a deposit on a flat, set up a business or get a car or similar. This scheme is based entirely on trust, and only people with a good reputation are allowed to participate.

Veronica's family used the Pardner scheme a lot in those early days in the UK.

When Veronica was small back in Jamaica, she fell from a verandah and injured her head. Her family didn't think her injury looked that bad and just gave her some sugared water (A Jamaican cure-all). They never took her to the hospital.

When she came to school in England, the teachers noticed something wasn't quite right and advised her to see a doctor. The doctor said that she had damage to the back of her skull, restricting the blood supply to her brain. The facilities in London meant that Veronica started getting the medical treatment she needed.

She had a seizure in her late teens and then had an operation to put a stent into the arteries in her neck head to improve the blood flow to her brain, which seemed to help at the time.

After school, Veronica worked in a factory in Battersea that made nurses' uniforms.

In her early twenties, when she was still living at home, Veronica got pregnant and had a baby girl. The relationship with the baby's dad didn't work out, so her mum helped her with the baby.

Although they were no longer a couple, the baby's dad would often call around in his bright yellow Triumph Dolomite and remained a part of Veronica and his daughter's life.

A few years later, Veronica met Winston at a house party. He was also from Jamaica and worked in a plastics factory in South London. They had a son and, in 1978, decided to get married.

Veronica's mum, Pearl, who by then was known as 'Auntie P', made the wedding and the bridesmaids' dresses. It was considered bad luck for Veronica's 7-year-old daughter Michelle to be a bridesmaid. Michelle remembers being jealous of her cousins getting dressed up on the day of her mum's wedding.

The pair married in St Barnabas Church on Clapham Common, and Winston bought up Michelle as his own daughter. Her real dad was still very much on the scene. In fact, he was good friends with Winston.

Veronica got on very well with Winston's mum. Her mother-in-law loved cooking and taught Veronica how to bake. Veronica was a quick learner and perfected the art of bun making and baking Caribbean Black Cake.

For many years Veronica worked as an Auxiliary nurse at Chelsea Hospital. She remained happily married to Winston for 37 years until he passed away in 2015.

Winston's death had a devastating effect on her, and she was 'quite lost' for a while, but a friend helped her through it and reintroduced her to crocheting, which she did when she was younger.

As Veronica got older, the accident she had as a child started to affect her cognitive function, and she had another seizure in 2021. She managed to get through it, but it affected her memory. The doctors said that Veronica should have had regular check-ups since that first operation when she was a teenager. Perhaps through some bureaucratic error, she received no aftercare support from the NHS and was left to get on with her life as best as she could.

Veronica retired from nursing at 60 and now lives alone. She crochets all the time and finds it relaxing and therapeutic. She also visits a local community centre where she meets other Caribbean elders, many of which are also retired nurses. They, along with her family have been a great support to her.

Veronica still loves baking cakes, and according to her daughter Michelle, who helped me with this interview, she 'still makes the best bun in Battersea'.

Gloria

Gloria was born in Jamaica in 1943. She came to the UK when she was just 15 years old. She says the reason she looks for good for a 76-year-old is that she ’no smoke, no drink and no bleaching’ (bleaching means -staying up late).

Gloria has had quite an eventful life. She used to be a model and appeared on several Reggae album covers. In the late 60’s she worked at Bobby Moores’ leather coat factory in Liverpool Street. She told me that the England legend would often come into the factory and that he was a 'decent man'.

She was working in Harrods when it was bombed by the IRA in 1983. Luckily she was in the canteen at the time on one of the upper floors so was unharmed. She’s worked for the Ministry of Defence and was working as a chef in Wandsworth prison in the 90’s during the infamous riots. Again, she was lucky that she was in a part of the prison that wasn’t affected.

She now owns ‘Gloria’s’ in Tooting Market which specialises in Caribbean groceries. The market is changing with lots of new trendy food stalls coming in but Gloria has her regulars and is doing good.

She loves living in the UK - ‘You will not find another country like this. If you are livin’ in England - You are livin’ good! - there’s nothing better than the English- I’m not going to ever live nowhere else’.

RIP Gloria ‘Miss G’ 1943-2022

Gloria is on the right.

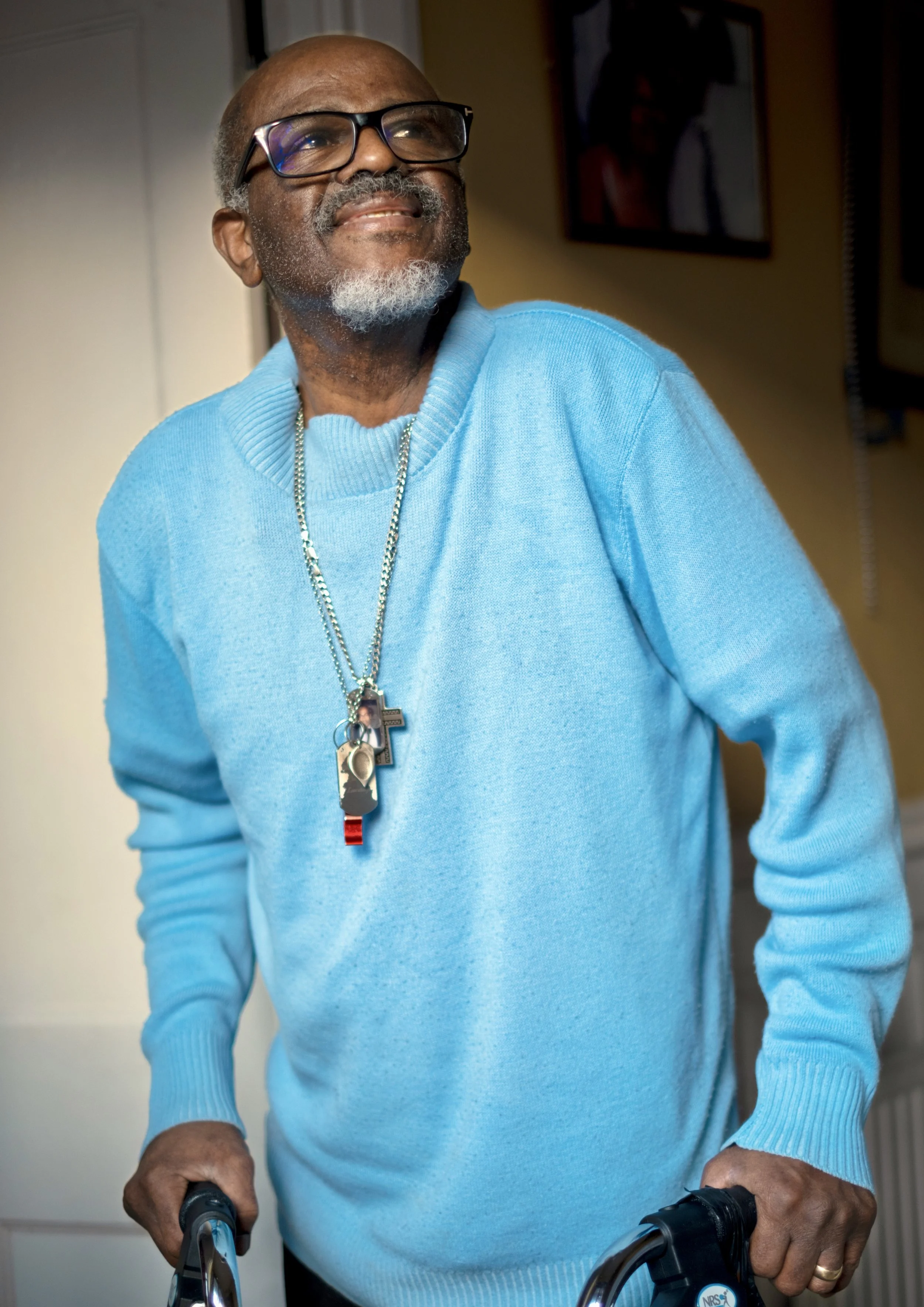

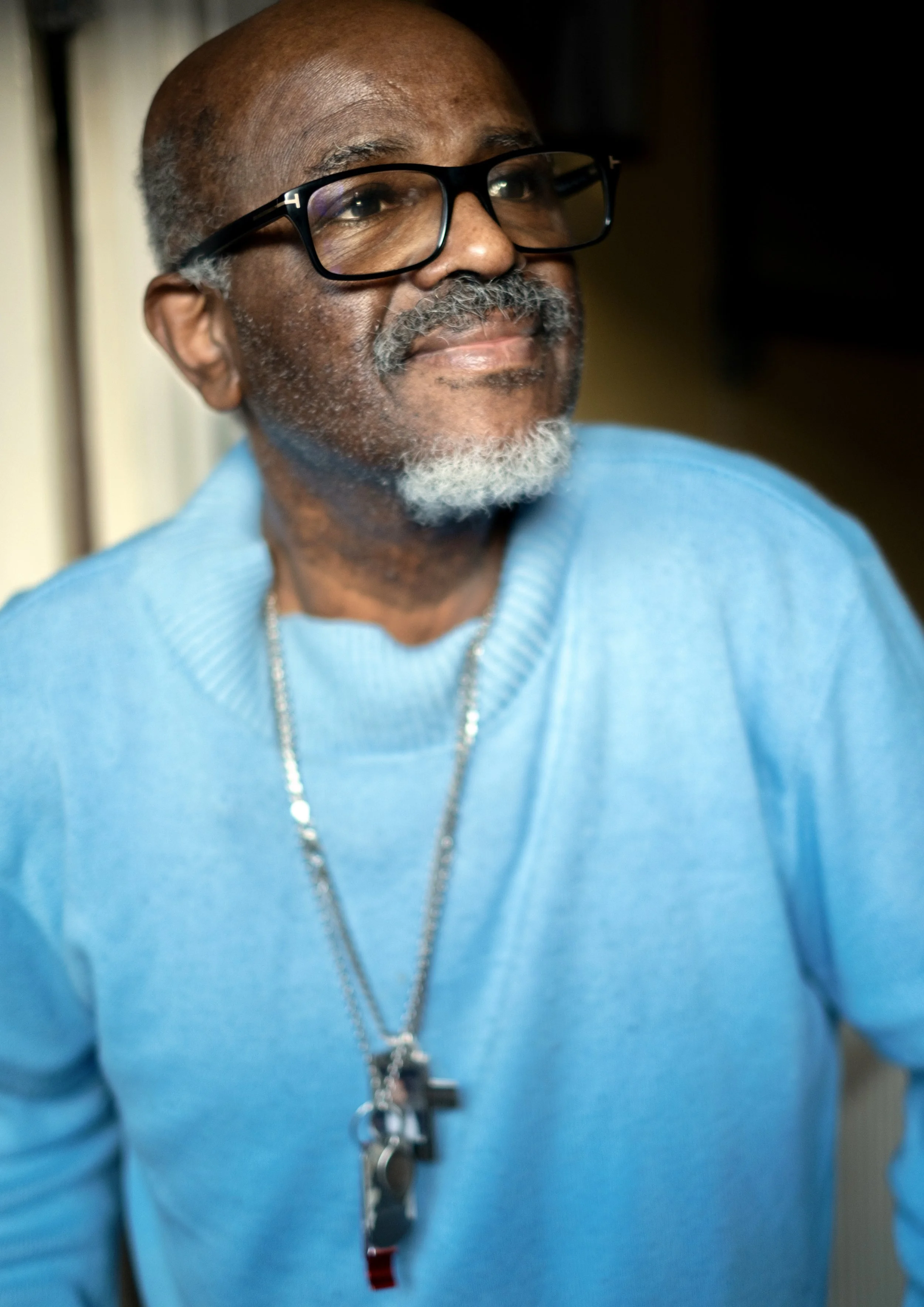

Manley

Manley was born in St Elizabeth, Jamaica in 1950.

When he was 8, his dad left for England and got a job working at a Lyons bakery in South London. A couple of years later, Manley's mum also left for England and got work in the ‘Tri-Ang’ toy factory in nearby Morden.

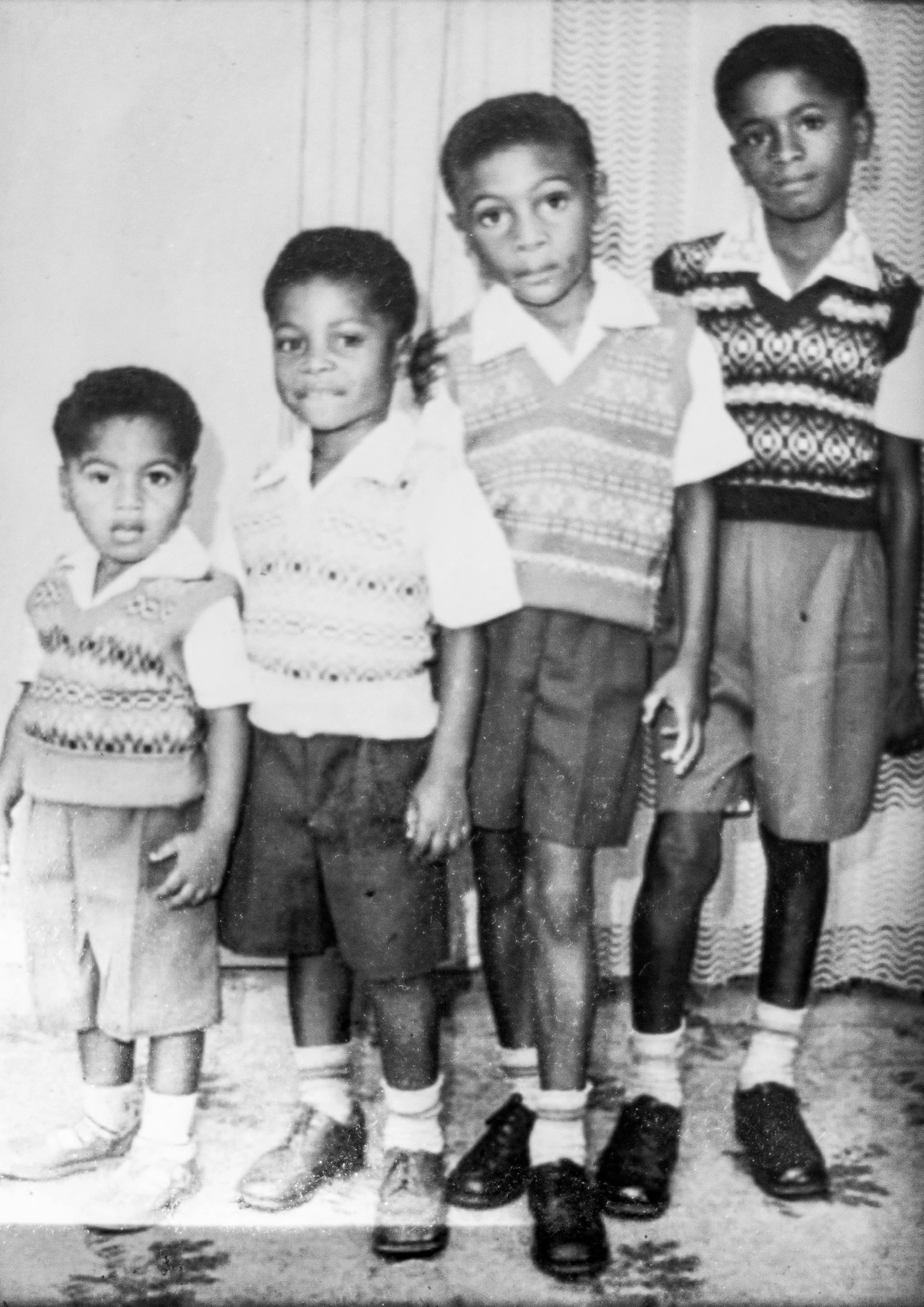

Manley and his three younger brothers went to live in the Jamaican countryside with their grandparents. He went to school "A little bit" It was strict, and they did a lot of caning in those days.

He also helped out on his grandparent's farm. There were hardly any vehicles in Jamaica back then, so they used donkeys to take the produce to the market to sell.

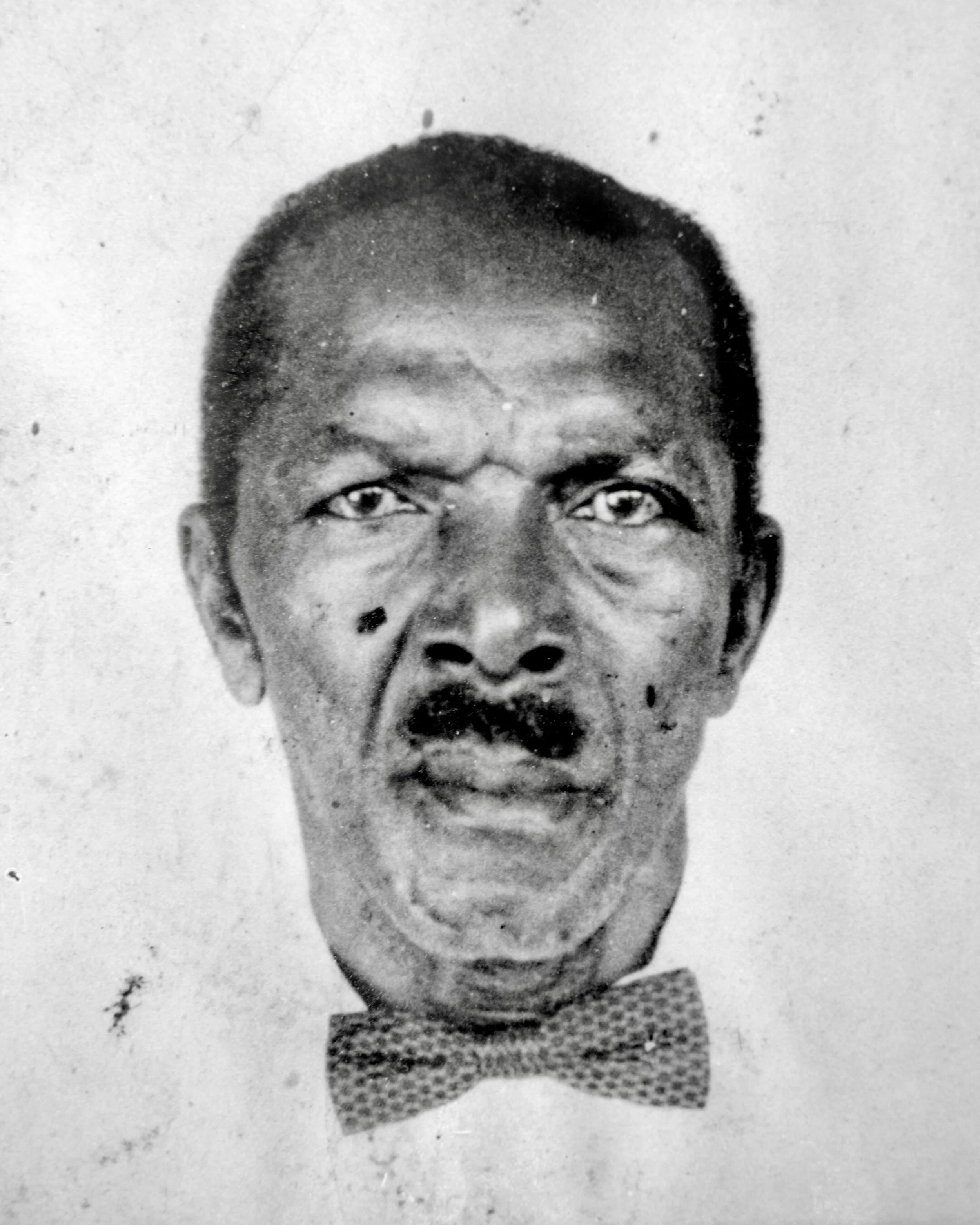

Manley’s grandfather.

Over in London, Manley's mum and dad had managed to save enough money to get a house and send for their sons. So, in 1964, the four boys were flown to England into London Airport. (Heathrow). An air hostess looked after the boys on the flight. Manley remembers that they didn’t eat much because the British food on the plane looked strange to them.

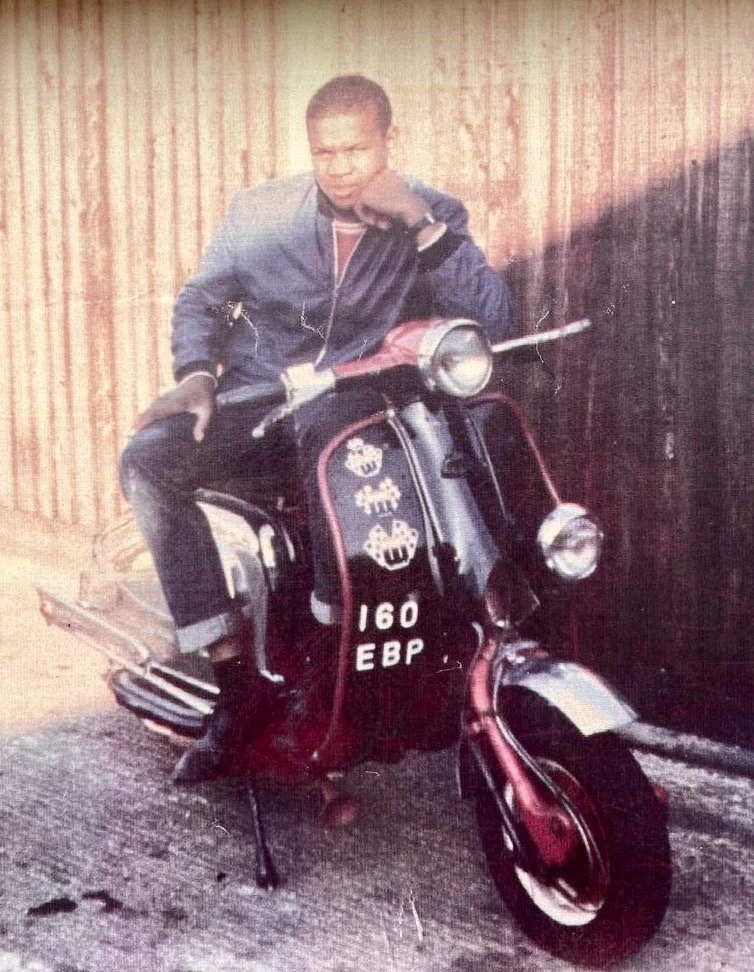

It was a cold British Winter with thick snow, and Manley remembers the milk being frozen in the bottles on the doorstep. He remembers the smog and the Teddy Boys riding around on their scooters.

Manley and his brothers went to School in Colliers Wood in SW London. He and his brothers were the only black kids there. The new school took a bit of getting used to and initially, there were a few fights, "You had to fend for yourself", but Manley made friends quickly. Like in Jamaica, the cane 'was in force' at this school too.

School got Manley into football. He and his new mates used to cross the river to Stamford Bridge to watch Chelsea play, and he still supports them today.

One of his aunty's husbands, who lived in Lewisham, had a Mini. They all used to all squeeze into the tiny car and go to Southend on Sea for an outing. He used to love going on all the fairground rides. It was a great childhood.

Manley (On the right) and his brothers just before they flew to England.

Manley left school at 16. He had learnt how to use a lathe and became an engineer. He worked for many years at Smiths Meters in Mitcham and knew how to make a gas meter from scratch. Manley's surname was Robinson, but everyone at work called him 'Robbo'.

Over the years, he had 19 jobs in total. Back then, you could walk out of a job and into another the next day. Most of the places are gone now. (A Lidl supermarket now stands on the site of Smiths Meters). Manley only ever worked in engineering - he knew how to take a car apart and put it back together again but not any more because they are full of electronics nowadays.

Life was good then. Manley gave his mum and dad a bit of rent out of his wages. He got paid in a little brown envelope and earned around 8 shillings per hour (50p). If he was lucky, he got a pay rise of 1p or 2p per hour.

He'd work all week and then go to dances. They were all over South London. The Brixton Town Hall dance, The Norwood Suite as well as house dances, with 100 people crowded into the room. There was never any trouble, and nobody got drunk. People would have these little glasses of whiskey or rum with a big lump of ice topped up with a splash of orange juice or whatever. Often the dance would go on all night. Sometimes he'd go from the dance straight to work. If he was lucky, he'd 'link up with a girl or get a 'rub up' dance,

Manley's wife Jenny was also from Jamaica, and just like Manley, she came to England in 1964. Manley was driving to work in his dad's Austin Cambridge when he first spotted her standing at a bus stop. From then on, he'd take the same route past the bus stop hoping to see her again. One day, he did, and he asked if she wanted a lift.

After dating for about a year, they married at Upper Tooting Methodist church.

The couple went on to have 3 daughters, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. They have been married for 50 years.

Manley has retired now. He's doing okay. He got a private pension from one of his engineering jobs and has lived in his house for 41 years.

He has a genetic condition that means he can no longer use his legs. He started to slow down when he was around fifty. The symptoms gradually worsened as he got older. The condition also affected his brother and his paternal grandmother. She spent much of her life unable to leave her chair, but lived to over 100.

For someone who used to love dancing, swimming, and playing squash (not very well, he joked), Manley is philosophical about his condition. "It's just a thing that runs in the family, and there's nothing I can do about it."

He calls his walker his 'third leg' and uses it to get about. "I've got to keep moving; exercise is what it's all about."

Manley goes out in his adapted car and tries to do as much as possible. He has always gone to church. He went with his mum from when he was small until she passed away aged 89, and he still goes to the local church every Sunday.

He likes to watch football on the TV and, for a treat, will make himself a 'Jamaican Guinness Punch.' A bottle of Original Guinness (Not draft) mixed with Nutrament (A milk-based energy drink) and shaken well with a large splash of rum.

Manley said that the last 69 years he’s spent living in England has been pretty good, and that he doesn't have too much to grumble about.

A few years ago, he took his mum on a long holiday to Jamaica. While they were there, they visited her sister who was celebrating her 80th birthday. It was great that his mum got to see her sister again because about a year or so later, both women passed away on exactly the same day - one in Jamaica and one in London.

Some Jamaicans dream of going back to the Caribbean when they retire, but not Manley, “I wouldn’t go back there to live, end of story. South London is my home.”

Betsy

Betsy came to Britain from Jamaica in 1960. She was just 16 and travelled all by herself. She flew in to Gatwick Airport and was put on the train to London where her Aunty was waiting for her at Victoria Station.

She got a job at a small factory in Old Street. They made sailor suits for little boys which were all the rage at the time.

After about 5 years, she got a job at a coat factory off Balham Grove and it was around this time that she met her husband Martin.

Life was going good, they had four children and managed to buy their council flat.

Early one morning Betsy and Martin were driving along Balham Hill when a drunk driver pulled out right in front of them. Martin was killed in the crash and Betsy was badly injured and spent 3 months on her back in Hospital. Martin was just 39.

Having 4 kids and no husband meant that Betsy had to work. Once she’d recovered, she got a job as an orderly at the Maudsley Hospital which treated people with severe mental health issues. She said that this was a very unpredictable job as some of the patients were highly volatile.

One day, she was doing the lunches and was pushing her trolley down a corridor, when a patient ran out of a room and put his arm around her. He squeezed her tightly, grinned and asked if she was okay. Betsy was terrified. She could see in his eyes that the situation could go badly wrong if she didn’t stay calm. She managed to control her voice and said, ‘Yes son, I’m completely fine.’

Eventually, some nurses led him away but Betsy had to sit down because she was so scared.

Betty is 78 now and retired. She has lots of grandchildren and has moved from Balham to Mitcham.

She has hip problems from the accident and still gets flashbacks from time to time. She said that even though it happened years ago, ‘It never really goes away.’ Despite this, Betsy remains a cheerful and upbeat person, ‘You just get on with what you have to do.’

John

John was born in Richmond, Jamaica, in 1935. He was one of 10 kids and had to share a bed with his brothers. His family lived close to the school, which was good because John loved school.

Once he’d completed his 'Senior Certificate of Education', which is the same as A levels in the UK, his parents then sent him to college at Buxton High School in Kingston, where he boarded.

After college, he got work in the accountant's office of the 'Citrus Growers Association of Jamaica.’ All the citrus growers in the country would bring their fruit to the warehouse, where it was packed and inspected. It was John's job to work out the value of each shipment before it was exported to the UK.

John said that Kingston was a fantastic place to live during that time, it was safe, and there weren't all the guns and violence that there is today. John enjoyed his job, and while working there, he met Audrey, his future wife.

He was keen to go to university but would have to pay for this in Jamaica. Whereas in England, back then, University education was free.

Audrey wasn't too pleased about him going, but John felt that England offered him more opportunities than staying in Jamaica.

He booked a flight to England through the Chinese travel service. In Jamaica, there is a large Chinese population. When slavery was abolished, plantation owners hired cheap Chinese workers to do the work of former slaves. Jamaica now has Chinese newspapers, schools, cemeteries, a Chinese freemasons association and even a 'Miss Chinese Jamaican' Beauty Pageant every year.

John flew into London airport (Now Heathrow) in 1961. The British houses all looked so strange to him. Everything was so grey and he remembers the fog. He said it was so thick that you could barely see at night. He thought it was wonderful when it snowed and would spend ages making snowmen. He didn't realise that he should have worn gloves and got chilblains. It was all so exciting and new. He missed his mum terribly, but she would write to him weekly in those lightweight blue airmail letters.

Initially, he stayed in a Hostel near Victoria Station. Then John went to live with an old school friend Oswald, who had come to England 5 years earlier and had a house in Balham with a spare room. They became lifelong friends, and he was the best man at John's wedding. They remained close until he recently passed away from Alzheimer's.

John got a job working behind the counter at the post office in Tooting.

Shortly after, Audrey came over and lived with an aunt in Clapham. She got a good office job and ended up working for Wandsworth Council.

After a couple of years, she and John married at St Anselm's Catholic Church in Tooting Bec. John was a Catholic, but Audrey was Church of England, so to get married in the Catholic Church, she had to get instructions from the priest about 'how to treat a husband well and how to behave as wife' (John joked that she has since completely ignored all this)

The couple got a mortgage from Greater London Council. In those days, the council would help people buy places. The couple still live in the same house today where they raised two sons who are now adults, with their own families.

Back then, the Post Office was state-owned, which meant John was a civil servant and could transfer to other jobs in the service while keeping his pension. In 1975 he became a VAT inspector in Shaftesbury Avenue in the West End of London, directly opposite Chinatown.

He would get the Northern line tube from Balham to Leicester Square every day and worked there for 20 years. He loved the job and was promoted to a senior officer. This position meant that he was allowed to retire at 60. John jokes that his bosses must be kicking themselves for the mistake of retiring people at 60 because he's now had a work pension for over 25 years.

He was always a member of the Labour Party and would help out by delivering leaflets and canvassing. The local MP, Siobhain McDonagh, said, "John, you are doing all this work. Why don't you become a councillor?"

John applied, and in the council elections, he won.

At 63, John became a councillor and worked mainly on the planning committee. There would be many long meetings to decide whether or not to approve a specific development.

Sometimes it was stressful because he'd have to reject some applications. It was also rewarding when he'd be out on the streets and see some of the buildings he had approved at the planning stage. John gave the go ahead to the construction of the Lidl Supermarket in Tooting. His wife shops there and says, "You can't go wrong with Lidl".

John is glad that he came to live in England. He has experienced racism. The worse time was in the 1980s when he and Audrey would worry about about their kids going out to play. His boys once got their bikes taken from them on Tooting Common by Skinheads.

He was a councillor for 20 years and became an honorary Alderman of London. "I've made my own luck. I don't sit around and complain about things like racism. It exists, but you must deal with it when facing it. You have to make more effort, but you must prove yourself."

John certainly proved himself because, in 2007, he became the Mayor of Merton.

At 87, John has retired from politics. But just like he has always done, he still canvasses and does leaflet drops on behalf of the Labour Party every Sunday. To him, it's the grassroots stuff that is important. He enjoys it.

He goes to a Keep fit class 3 days a week, and his wife insists he keeps the house up to scratch with painting and fixing things up. He's currently enjoying reading Michelle Obama's latest book.

John never did go to university as planned when he first came to the UK. Judging by all that he's achieved in the last 63 years, it's hardly held him back.

Marjory

Marjory was on her way home from the shops when I asked if I could take her photo. ‘Yes, dear’ she said.

She was born in Barbados but has lived in Balham for most of her life.

I asked her how The UK has treated her? She paused for a long time before answering and said, ‘England is what you make of it’. Before I could respond, she walked off.

FLOWER

When Isabella was born, her big brother said she was as pretty as a flower. The name stuck, and everyone still calls her Flower 86-years later.

Flower was born in Guyana. Her maiden name is Quain, which is an Irish name. Her great-grandfather was Irish but returned to Ireland at some point, and the family lost touch with him. Many of Flowers relatives have very light skin because of this.

At 25, Flower came to the UK to work as a nurse. This was in 1961. She flew from Guyana to Trinidad and then got on the SS Kenya. After stopping at several Caribbean Islands, she headed to the UK.

Everyone got seasick, but she made many new friends.

On the voyage, the ship was diverted to a small port in Portugal. When all the passengers got off to have a walk around, the locals were terrified because they’d never really seen so many black faces before. Flower and her friends thought that this was hilarious.

Once she finally got to the UK, She was posted to the Waddon Hospital near Croydon and her training as a nurse began.

She was given staff quarters and a uniform which consisted of an apron, cap and some heavy leather shoes. Every morning, the new recruits had to stand to attention in front of the matron. She would check that their uniforms were starched, their shoes shiny, and their fingernails were short. The matron was Scottish; Flower told me she was strict but friendly.

There were about 8 new nurses in total. Some were from Jamaica, some from St Vincent and some from Ireland.

She remembers part of her training was in an orthopaedic ward. The matron made her and a fellow nurse sit on each side of a man whose hand would involuntarily shake, and his hand kept rubbing Flowers thigh. She and her friend desperately wanted to laugh, but the matron was watching to check that they were taking her role seriously.

Once she passed her SEN exam (State Enrolled Nurse), she was told she would get paid £9 per month. Flower cried because of this so little money. After a while, Flower gained experience, and her salary increased.

In 1984 the Waddon hospital was closed, and Flower moved to Balham.

She met her husband at a dance party. But told me that he was, ‘A very naughty man.’

Unfortunately, Flower never had any children. She had a bad back from all the strenuous nursing work, which caused her to always miscarry.

Her husband went off years ago, and Flower doesn’t know or care where he is now - ‘I was always busy with my work.’ She told me.

In Balham, she worked at St James Hospital, which was demolished after a few years too. She ended up working at St Georges in Tooting. She said working at smaller hospitals like the Waddon and St James was wonderful because you could get to know all the staff and the patients. She wasn’t so keen on working at huge hospitals like St Georges.

Flower loved being a nurse. She’s retired now but managed to buy her own flat and enjoys doing crosswords and watching news programmes on TV.

When she was sixty, she adopted her great-nephew when he was just 36 weeks old. He’s now 24, has just finished a sports degree at Uni and has a job as a manager in a local leisure centre. Flower is his mum, and she is so proud of the man he has become.

Stan

When his dad left Jamaica to get work in England, Stan was sent to live with his grandparents in St Elizabeth to the SW of the island.

His grandfather passed away shortly after, so Stan was bought up by his grandmother, who owned a shop and his auntie, who worked in nearby Appleton, where they make the famous rum.

Stan did well at school and wasn't a naughty boy - 'You can't be naughty when you have Jamaican parents' But by the time he'd got to 17, he'd become too much of a handful for his grandmother, so he was sent to England to live with his dad.

Stan took the boat from Kingston to Italy and then had to get the train across Europe back to London.

His dad lived in a house in Balham with his new wife. (He had had split up with Stan's mum). Stan moved in with them and got on well with his dad's new partner.

Stan hoped to continue his education, but his dad told him to get a job. So he started out working for a firm doing the sweeping up. He then got a job in a factory that made batteries before getting a job at Royal Mail. His round was on Lavender Hill in Battersea, and he loved the job. He got to know the residents and would often help out if they wanted their shopping carrying or needed their milk bringing it.

Battersea changed so much during the time that Stan worked there. He saw the start of the gentrification of the area with new people and shops moving in. During his time as a postman, Battersea Power station, which always belched smoke from its iconic chimneys, shut down for good. The Power Station is now a shopping centre.

Stan said that most people were friendly, but there was also racism back then.

The Teddy Boys were the worst. They'd always be on the lookout for targets. He remembers being on his round and emptying letters from a Pillar Box when a group approached him. Stan said something, and as soon as they heard his accent, one of them said “Let's not bother; he's Jamaican.” Jamaicans had a reputation for fighting back, so they left him alone.

Stan also used to love football, but the National Front and the racists amongst the fans at Chelsea FC put him and a lot of his black friends off from going.

One day, he was helping a friend fix a car and saw "a lovely young girl walk by." He said, "I haven't seen you around here before. Do you want to maybe come to the pictures one day?" Her name was Jennifer, and they went to see a film at the Odeon cinema at Clapham South which has since closed down and is now a wine merchants.

After 3 years of dating, the couple got married and have just celebrated their 53rd wedding anniversary. They have 2 grown-up kids and 2 grandkids.

Stan has always been a member of the Labour Party and used to go to the conferences. At one of these, he met Gordon Brown MP who went on to be Prime Minister.

He retired from Royal Mail after 45 years of service. He got a tie and cufflinks as a leaving present.

Stan has always been interested in politics and the local community, so once he'd retired, he decided to put his name forward as a local councillor. He was selected, and in the council elections, he won and helped turn the area from Conservative to Labour.

Campaigning in politics is about talking to the public and knocking on people's doors when canvassing. All those years as a postman going door to door meant that Stan was a natural, and he went on to win the next election too.

Stan retired from politics but not before becoming deputy mayor between 2017-2018. He'd give out citizenships, go to openings, and visit elderly people and hospitals.

Stan loved being a councillor. It was challenging and stressful sometimes, but Stan found it so satisfying when his work meant he could make a difference and help local people, Just like he did over 50 years ago as a young postman when he'd help the residents out on his round.

Gloria

Gloria is 87 and was heading to Holy Trinity Church on Clapham Common when I took this shot.

She was born in Jamaica and came to live in Coventry when she was small because her dad, who was in the RAF, was based there.

She worked for most of her life in The Department of Social Security as a clerical officer. She had four daughters, but sadly, one died at 56 from brain cancer.

One of her daughters bought her the walking stick after she had a fall. Gloria was wearing her high-heels at the time and tripped when she was rushing to cross the road. She loved those high-heels and told me that she would be wearing them today if she hadn’t had that fall.

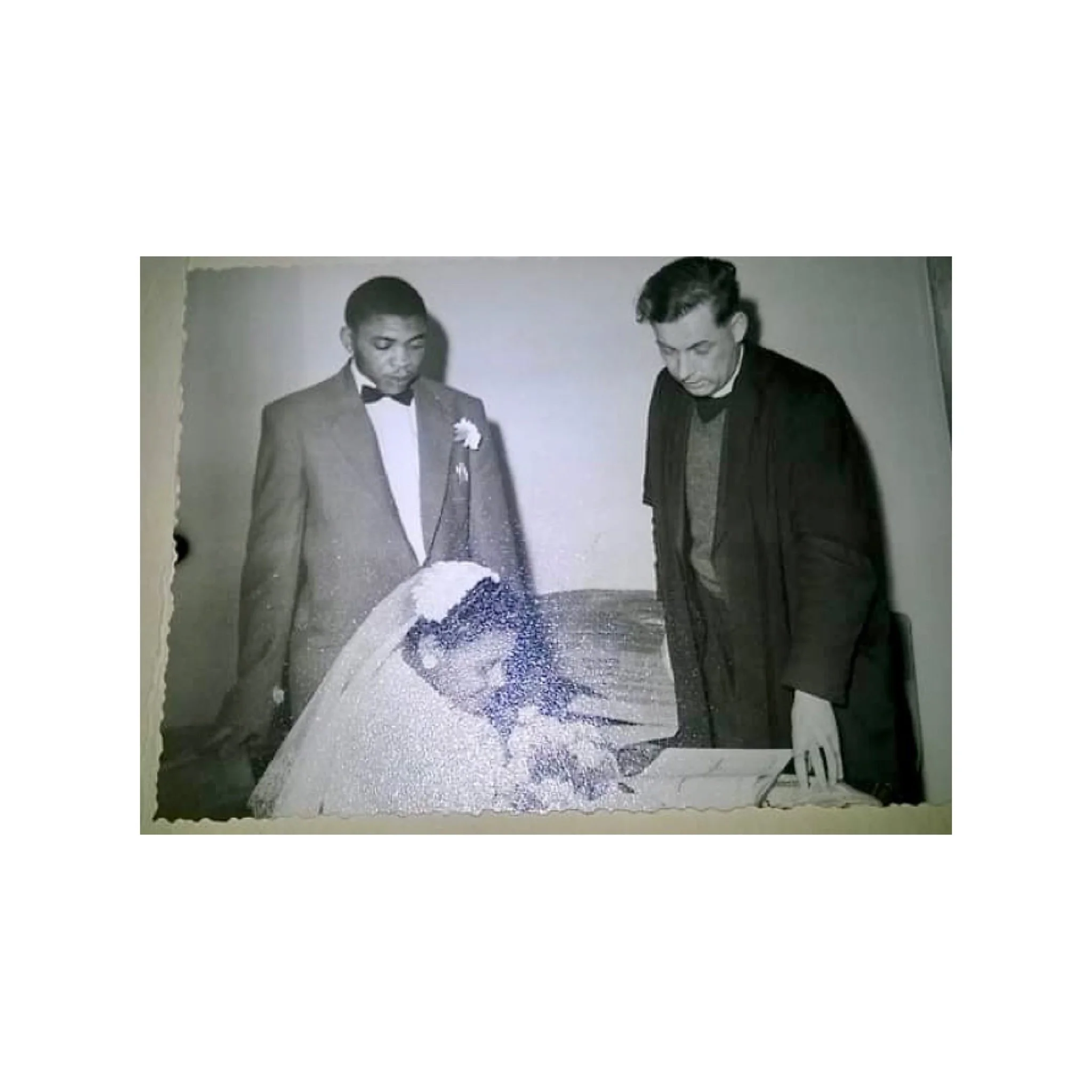

Gloria’s wedding in Coventry.

Hector

'I like to start early before the sun gets too hot - I take my time and enjoy the work’

Hector is 73. He’s originally from Jamaica but has lived in Battersea for most of his adult life.

Before retiring, he worked for British Rail. After years of renting a place to live, he managed to save enough to get a mortgage on the house pictured above where he has lived for the past 30 years.

Hector now owns the house. He told me that he does all the decorating himself, 'I like to start early before the sun gets too hot - I take my time and enjoy the work’. He told me that his road has changed quite a bit over the years. He used to have a lot of West-Indian families as neighbours, but Hector, his wife and grown-up daughter, are now one of the last. ‘My friends all sold up years ago when the house prices started going up - but we didn’t want to leave’. Hector's decision to stay was quite a good one because the prices have continued to rise, and his house is currently worth around £1.7m. Hector's not selling up any time soon though, ‘It’s my home and it’s got my soul in it’ he said with a smile before going back to working on his windows.

Yvonne

Yvonne came from Guyana to the UK when she was 12 or 'Something like that.'

She went to Overhill school in Plough Lane, Battersea.

After leaving school, she got a job at the Decca factory in New Malden. She worked on the wiring for radar systems that would end up in aeroplanes and boats. (Decca did electronics before they got into making records).

It was complicated and fiddly work. One day, the then Prince Charles visited the factory and started talking to Yvonne. She can't remember what he said because she was so nervous. She does remember the photographers all wanting her to look up at the Prince, but she was too busy concentrating on her work.

She had a copy of the newspaper clipping in her shopping trolley and showed it to me. She said that the Prince seemed nice.

She used to go back to Guyana every year to see her relatives, but not for the last few because 'The Covid clip our wings.'

Yvonne is 77 and she loves to dress well - her coat is a Burberry. She also loves to sing at the local Methodist church near her home in Balham.

She has two daughters, and even though, 'They got their own fish frying,' they come to visit her when they can.

Yvonne’s work was fiddly and she had to concentrate.

Victor

In 1954 Victor came from Barbados to the UK on the 'SS Columbia.' He was just 20 years old.

It was tough being black in Britain back then. He'd turn up to a job interview and would be told, "The job has gone." He heard one of his prospective employers say, "Why'd d'you send him here? You didn't tell me he was black."

Eventually, Victor got a job as a carpenter, but not long after, he was called up for National Service and sent to Cyprus, where he served as a medical orderly.

After returning to England, he continued to work as a carpenter and saved up enough to buy a house close to Wandsworth Common in South London. Back in the early 60s, homes were cheap in the area. One of his new neighbours said nobody wanted to live in Wandsworth. 'The snooty-nosed people want to get through it as quick as possible on their way from the city to their country houses.'

According to Victor, Wandsworth is the best part of London - it has the most hospitals, the most schools and the best railway station, saying, 'you can get anywhere from Clapham Junction.' He added that Wandsworth has the only reference library in the UK that opens on a Sunday. Victor used to enjoy reading, but his real passion was dancing. He loved ballroom and did lessons at a dance school in New Cross. He'd do the Waltz, the Tango, the Rumba, the Foxtrot and the Pasodoble and can still remember some of the moves.