‘Born for the boat’

Real life stories of the Irish diaspora.

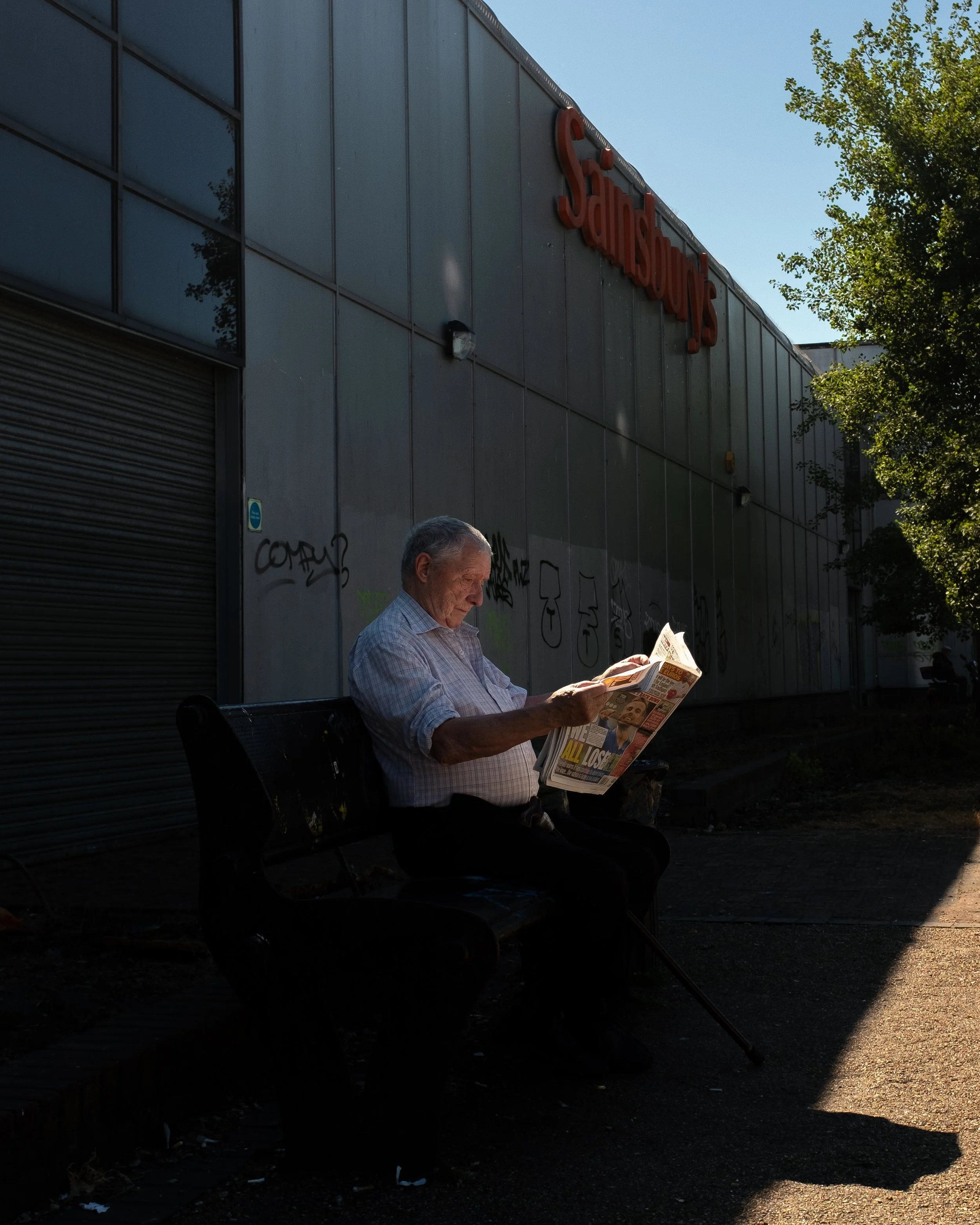

SEAMUS

When Seamus came to London from County Leitrim, he settled in Kilburn. At first, he had to share a room with another Irish bloke, but as soon as he got a job and some money together, he got his own place.

Initially, he worked at the Smith’s Instruments Factory in Cricklewood, making car speedometers. He then worked on the building sites before moving into the tarmacking trade. He preferred this as the money was good, and there was always constant work. He continued working in tarmacking until he retired at 70. He told me it's a hard job at first, but it gets much easier once you get the knack of it.

Back when he first came to London, the men from Leitrim tended to stick together and they’d go to all the dancehalls around Kilburn and Cricklewood. One evening, for a change, they decided to go down to South London to the Harp Dancehall in New Cross (now a nightclub called 'The Venue'). It was here that Seamus met Nora. She was from Donegal and was working at the local Woolworths.

Seamus and Nora clicked, and not long after, they were married. They bought a house together in Forest Gate and had a son and a daughter.

Life was good, but in her mid-40s, Nora became unwell, and when she was just 47, she passed away. The kids were at university at the time. So Seamus was on his own. Seamus admitted that around then, he started to drink. It was probably the loneliness. A couple of falls made him realise his drinking was becoming a problem, so he quit and hasn't touched a drop since.

Seamus has never got romantically involved with another woman since Nora passed away. He didn't want to upset his children. He told me that, even now, when they have their own families, it still wouldn't feel right to him if they ever thought that he’d replaced their mum.

Seamus has done well. He has raised 2 university-educated kids. One is an accountant, and the other is a teacher. He owns his own house and has a small pension. He now has 8 grandchildren and gets to see them often. He has no regrets about moving to England. "I always did well in London and always found a good place to stay. Any trouble I got into was my own fault."

Seamus plays bingo at the Irish centre. On the day i was there he won. The prize is getting back the £3 he paid for his lunch.

Patricia

Patricia Mary Walsh has always been incredibly proud of her Irish heritage. So much so that she even gave her dog an Irish name.

Pat adored animals and couldn't bear to see them harmed. She was a vegetarian back when it was generally frowned upon and way before it became fashionable. She was always popular at mealtimes because rather than make a fuss about being a vegetarian, she would simply transfer whatever meat she was given to the plate of the person sitting next to her.

Pat worked for many years as a civil servant, and it was while in the service she met her husband, Ken, who was originally from The Czech Republic.

Ken converted to Catholicism to marry Pat. They tied the knot in Westminster Cathedral. Ordinary people are allowed to marry in the crypt.

Ken was 6'7. During WW2, he was a radar operator in the RAF. Being so tall, he often recollected how difficult it was for him to fit into the tiny radar cockpit on the planes.

The couple had a happy marriage, but when Ken was in his early forties, he got cancer and passed away. The couple never had children.

Pat became an English teacher at Bishop Thomas Grant Catholic School in Streatham, SW London. She enjoyed the job and went on to become the deputy headmistress.

Pat was a voracious reader and always loved teaching and learning.

She often attended evening classes where she studied Russian and Gaelic.

Even in her 80s, she had no problem operating computers. She also loved travelling and enjoyed a trip to Prague just before her 90th birthday.

Pat was a good Catholic and always helped out in the community.

Right up until she was in her 90s, she often took local elderly people to hospital appointments. (Many of whom were younger than her)

A local priest had lost his sight, so Pat recorded 'The Daily Office' on tape for him to listen to. (The daily office consists of the various prayers a devout Catholic recites daily).

Although she was still physically and mentally fit, the death of her beloved dog had a profound effect on Pat. She sold her house in Dulwich and moved to the assisted living section of a care home, where she continued to live independently.

In 2010 the Pope visited the home, and Pat got to meet him. She was wearing a blue suit that she made herself as she was also a keen dressmaker and often made her own clothes. She enjoyed meeting the Pope and recalled that 'he was a nice little man.'

A few years later, a fall took away Pat's confidence, and she moved into the nursing wing of the home.

Pat is now 101 years old.

Over the last couple of years, she has developed dementia. The onset was quite sudden and severe.

Unfortunately, the once fiercely intelligent Pat is no longer able to communicate.

I wrote this interview thanks to the help of Pat's closest friend Olga, a music teacher. The pair met almost 40 years ago, shortly after Pat retired when typically, Pat decided that this was a good time for her to learn how to play the flute.

Pat meeting the Pope in the blue suit that she had made herself.

Peter

Peter was born in 1951 in County Meath.

He’s worked most of his life as a mechanic, so there was always plenty of work for him in Ireland.

He only came to England in the late 80s to be near his family, who had all moved there before him.

They’ve all since gone back to Ireland, but Peter now has an English girlfriend, so he’s staying put.

Bridget

Bridget was born in the countryside close to the village of Kilbarron in County Tipperary.

When she was 18, she met Michael at a dance. She 'liked everything about him', and it wasn't long before they decided to get married.

Her dad said she was too young. He said to Micheal, "You seem like a nice lad, so why don't you come back in a year and ask me again."

But Bridget was certain that Michael was the man for her, so the wedding went ahead. She remembers the day of the wedding. Everyone was waiting at the church; it was just her and her dad about to set off. Her dad said, "Bridget, it's not too late. We can come out of here and turn left to go to the church, or we can go right and drive to Dublin and have a holiday."

Bridget turn left and she and Michael were married.

Like most young people in the village, it wasn’t long before the couple came to England looking for work.

They settled in Forest Gate in the East End of London. They rented some rooms in a 'lovely' house. An Irish family lived on the floor above, and another lived on the floor below.

Michael got work labouring and started night school to train to become an engineer. He was determined to make the most of the opportunities available from living in London.

Bridget got work at the Matchbox Toy factory in nearby Hackney. At the time, Matchbox was the largest die-cast toy maker in the world. Bridget had to put the miniature toy cars in their boxes as they came along the production line. She struggled to keep up but didn't work there for long because she became pregnant. Michael insisted that she stop working and rest at home. "He wrapped me up in cotton wool to stop anything happened to his precious cargo."

Not long after, Michael noticed a lump in his neck. He went to the doctor and was diagnosed with advanced Hodgkin Lymphoma, an aggressive cancer of the lymphatic system. Nowadays, it's one of the easier cancers to treat. Chemotherapy treatment for this type of cancer was just being developed then, but Michael could not have been saved. The doctor and Bridget decided not to tell Michael that he was terminal. He seemed to know anyway and said he wanted to return to Ireland.

He passed away a few months after coming home. He was just 27, and Bridget was 22. Bridget will never forget standing in the graveyard with the veil blowing around her face in the wind. She felt so utterly alone. She was six months pregnant.

Bridget had an older brother, Gerry, who was also living in England. After the funeral, he said there was no way he would leave her stuck in a tiny village in the middle of Ireland. "If I leave you here, you'll sit in that chair for the rest of your life with rosary beads around your neck."

He'd already bought her a ticket, so she went back to England and lived with him and his wife.

Once she was back in London, she became unwell. She had severe Toxaemia (now known as Preeclampsia) and was taken to the hospital. When she was close to her due date, she haemorrhaged. The doctor said that she was too unwell to have an anaesthetic, and she was rushed into the operating theatre. Her baby, Jacqueline, was born perfect.

Bridget was a young single mum living with her brother and his wife; this wasn't a long-term solution, and she needed to get her own place.

Luckily, while she was at the hospital, she bumped into Doctor Choudhry. He had looked after Michael during his cancer treatment. When he saw that she had the baby, he said she could live in the flat above his practice and run the surgery downstairs.

At that moment, Bridget had a job and somewhere to live rent-free. Dr Choudhry lived in the big house opposite the surgery. He was a middle-aged man who had never married and didn't seem interested in women, but he treated Bridget like his daughter.

Bridget worked hard and saved every penny. At the weekends, she would leave the baby with her brother and his wife and work as an usher in a cinema in nearby Ilford to earn extra money.

For those first 5 years, she was too full of grief to have any social life. The only outing she'd ever go on was to a cinema in Brick Lane to watch a Bollywood film with the doctor. She didn't understand a word of it, but she loved the dancing and the music.

When she was 28, she had saved enough money to buy a house in Ilford. At first, it was just her and Jackie, but then she took in lodgers who lived upstairs to help pay the mortgage. They were 'two lovely Irish fellas' who kept themselves to themselves and never gave her any trouble.

Once her daughter was older, Bridget started to go out a bit more. She'd go to the dance halls with her brother and sister-in-law. She passed her driving test first time and started socialising.

She never had any proper romantic involvement with other men. She didn't want to overcomplicate her daughter's life. While her daughter was living at home, she wouldn't consider changing the status quo, "my daughter always came first; it was just how I was bought up.”

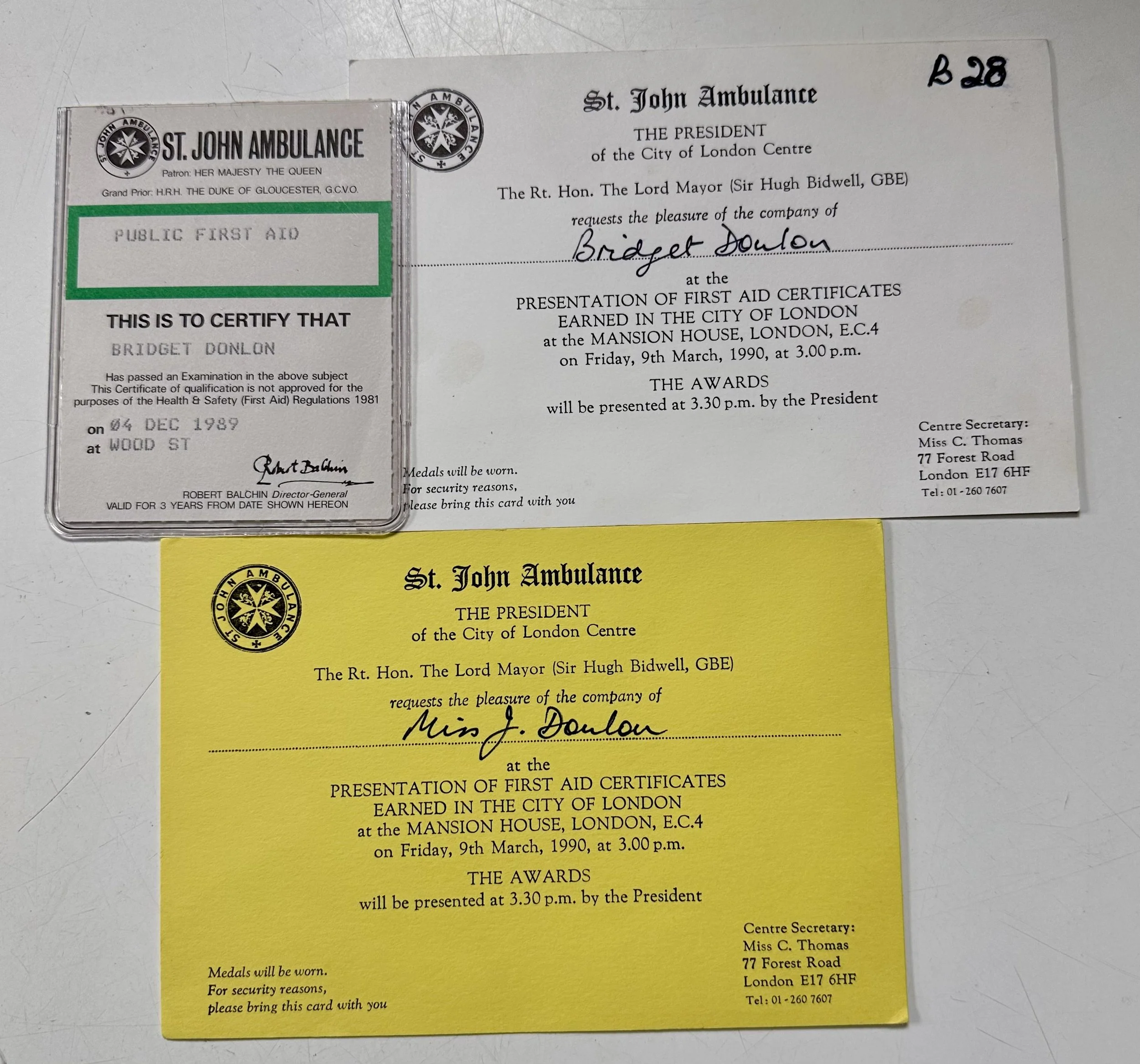

She then worked for Social Services and did ambulance training. A hospital for the elderly was closing down, and all the patients had to be transferred. This was done at night when the roads were quieter, and Bridget would drive the ambulance and move the elderly patients from the old hospital to the new. This was exhausting but rewarding work.

Bridget learnt how to drive an ambulance.

Bridget’s daughter did well at school and decided she wanted to become a dentist. So Bridget sold her house and used some of the proceeds from the sale to help pay for her training. Bridget bought a flat in Hackney. It was an ex-council flat, and she paid just £28,000 for it.

Her investment in her daughter paid off because Jackie now works as a dentist in Rhode Island, America. She often comes over to visit Bridget. Bridget is retired now, but she likes to keep busy. She volunteers at Irish Elders Centre in East London. She sold her flat in Hackney and now lives in a modern apartment overlooking the river.

She is proud of how well she has coped mentally over the last fifty years. Moving to a new country and losing her husband when pregnant, and then bringing up her daughter alone. "Behind every smile is a sadness. Michael and I were good souls, but it just wasn't to be."

Bridget volunteers at the Irish Lunch Club.

JOAN

Joan is 88. She came to London from County Laois in 1951 when she was just 16.

She started out working as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in Golders Green. The family were lovely and she quickly got used to living in London.

She’s always lived in Fitzrovia, an area just north of Soho in the heart of the capital

Joan still loves the area, but all her Irish friends have either ‘moved away or passed away.’

Mary Boyle

Mary rose Boyle was born in County Monaghan in 1925

She's named after her 2 grandmothers, Mary and Rose, although nearly everyone calls her Mary. Her parents were farmers. They had horses, pigs and cows. There was potatoes to sew and corn to cut but according to Mary, "There was nothing hard about it, we had a lovely life." She remembers springtime, running home barefoot from school through the meadows. She remembers the snow being so deep in the winter that her dad would come and meet her at school. She can still picture him now, shivering under a tree as he waited.

Mary was the eldest of 5, and her village was right on the newly formed border between Southern and Northern Ireland. A little stream ran through the meadow, and the border ran through the middle of it. Mary told me that you could stand in a different country with each foot.

Mary remembers there being a lot of smuggling. Things were either cheaper or more expensive on one side of the border than the other. She’d be awoken in the middle of the night by the sound of pigs or cattle being driven across. One morning, her dad found a young heifer standing shivering next to one of the houses. It must've separated from the herd, and the smugglers hadn't noticed. Later that day, someone appeared and sheepishly asked if anyone had found a cow.

Her village was in a remote place, but a soldier would come and stand guard. Her house was about 15 yards from the border. They'd use the stream water for washing, but if they wanted drinking water, they had to use the spring which was in Northern Ireland. Mary remembers taking the bucket to the guard and asking him to fill it up as they weren't allowed to cross. She said her mum would often make him a cup of tea as she felt sorry for him standing alone in the middle of nowhere.

When Mary became an adult, there was nothing to do in the village. So she got a job as a 'mothers helper' in Belfast. Mary loved her time there and remembers sitting on the banks of Loch Belfast at Green Island on long Summer evenings. She remembers the foghorns on the boats going by on misty mornings. Mary also loved dancing and loved to go to the dance halls at Whiteabbey.

She also worked as a housekeeper and carer, helping elderly people in their homes. It was a responsible job, but being the eldest of 5 and growing up in the country, it was just one of those things that all country girls did.

Two friends of hers, Sade and Susan McKenna, decided to go to England to work, and Mary was supposed to go with them. The timings didn't work out, so the sisters went first, and Mary followed sometime later. She remembers it being a rough sea crossing, and she couldn't sleep at all. People were so seasick they were lying on the deck. This was followed by a long train journey from Holyhead to Euston. Mary remembers being squashed up against the window the whole trip by a huge man on the packed train. She arrived in Euston at 7am, exhausted and desperate for a cup of tea and a night of sleep. She'd arranged to meet a friend who she had been exchanging letters with and wandered around for ages before she eventually found her.

Mary's first job was at one of the most exclusive addresses in London. She worked as a mother's helper in 'The Boltons' in a mansion owned by Russian aristocrats. It was quite a shock for Mary to be in such opulent surroundings and the indoor toilets and baths were a novelty. She was told to wear trousers for the job and was sent to the local shop, Harrods, to get them. Again, Harrods was like nothing she's seen before back in Ireland. Mary’s friends thought her trousers were very posh and she often lent them to anyone who was going out somewhere special. Mary’s group of friends working in London all came from her part of Ireland. They tended to stick together and often met up and went together to Irish dances. It was at a christening that she first met Patrick.

He was raised in an area close to Mary's village but north of the border. She already vaguely knew his family. When she took him back to Ireland to meet her mum, it turned out that her mum had been to school with his.

The couple married in 1951 and rented a small flat in Camberwell in South London.

Patrick worked at the Henry Ford factory in Dagenham. Every day, he would get up early and take the first bus out of Camberwell into Central London where he'd get the tube east to Dagenham. He did shift work making car parts. He said that it felt like 'The whole of Ireland' was working at Fords.

Mary had four kids. The flat had no bathroom, so they'd wash in a zinc tub. Luckily, they also lived directly opposite Camberwell baths and her kids made good use of the swimming pool. Despite the flat being small, Mary always made sure that there was room for people coming over from Ireland who needed somewhere to stay. She hosted her brothers when they came to start a life in England, as well as other people from the village doing the same. Mary said that it was just how it was back then. She remembered the feeling of first turning up in England from Ireland, so was always wanting to help out.

Her dad also came to stay with Mary and Patrick when her mum passed away. He stayed for many years until he went into a nursing home.

The family stayed in the flat until 1972, when it was demolished to make way for the new London Magistrates Court. Mary and the family were rehoused in a council house near Denmark Hill with a lovely garden, bathroom, and two WCs.

About this time, Mary's sister-in-law got a job working for a high-class caterer and would often ask Mary to help by doing a bit of waitressing. Mary told me she met, “All the Hob-Nobs” through this. Once, she was standing at a function holding a silver tray of quail eggs when she was tapped on the shoulder. When she turned around, it was the Queen wanting one of the canapés. Mary enjoyed this job, and an extra bonus was that they'd often be given lots of luxury food items that weren't used at the events.

Patrick retired from Ford in his early sixties. He’d dedicated his entire life to working at the factory, and when work finished, he was bored and would often say, "I will be dead within a year." He really did believe this. If the house needed something new, he'd say, "what's the point? I won't be around much longer anyway." He then started to do a bit of gardening. At first in his back garden, but then for some of the big houses in nearby Dulwich. His reputation grew, and more wealthy people wanted him to do their gardens. It was like a second life. He then took up cooking, got into football and even home brewing. He continued gardening right up until he was in his eighties. He passed away at 94, over 30 years after retiring.

Meanwhile, Mary got into knitting and then sewing. She was the first on her street to have a knitting machine and always made clothes for her relatives. The wife of Mary's eldest son, Michael, died very young of breast cancer. Mary would look after her 6-year-old granddaughter Claire every night after school until Michael got home from work. Mary said it was lovely spending so much time with her young granddaughter.

Mary is 97 and now lives in the same care home that her dad went to. She said living in a care home isn't ideal, but she knows it's the right place for her as she is no longer able to do her own shopping and was starting to worry about having a fall when she was at home. She makes sure she does a couple of circuits around the care homes garden every day, as it's important to her to keep active. The home is run by nuns, and Mary says they are lovely. She goes to mass every morning. Faith has always been a part of her life, and she cannot imagine not having a religion.

Mary feels that she has had a good life. She doesn't feel like she has had any real problems over the years, and as she put it, "I can safely say everything went 'hunky-dory.'"

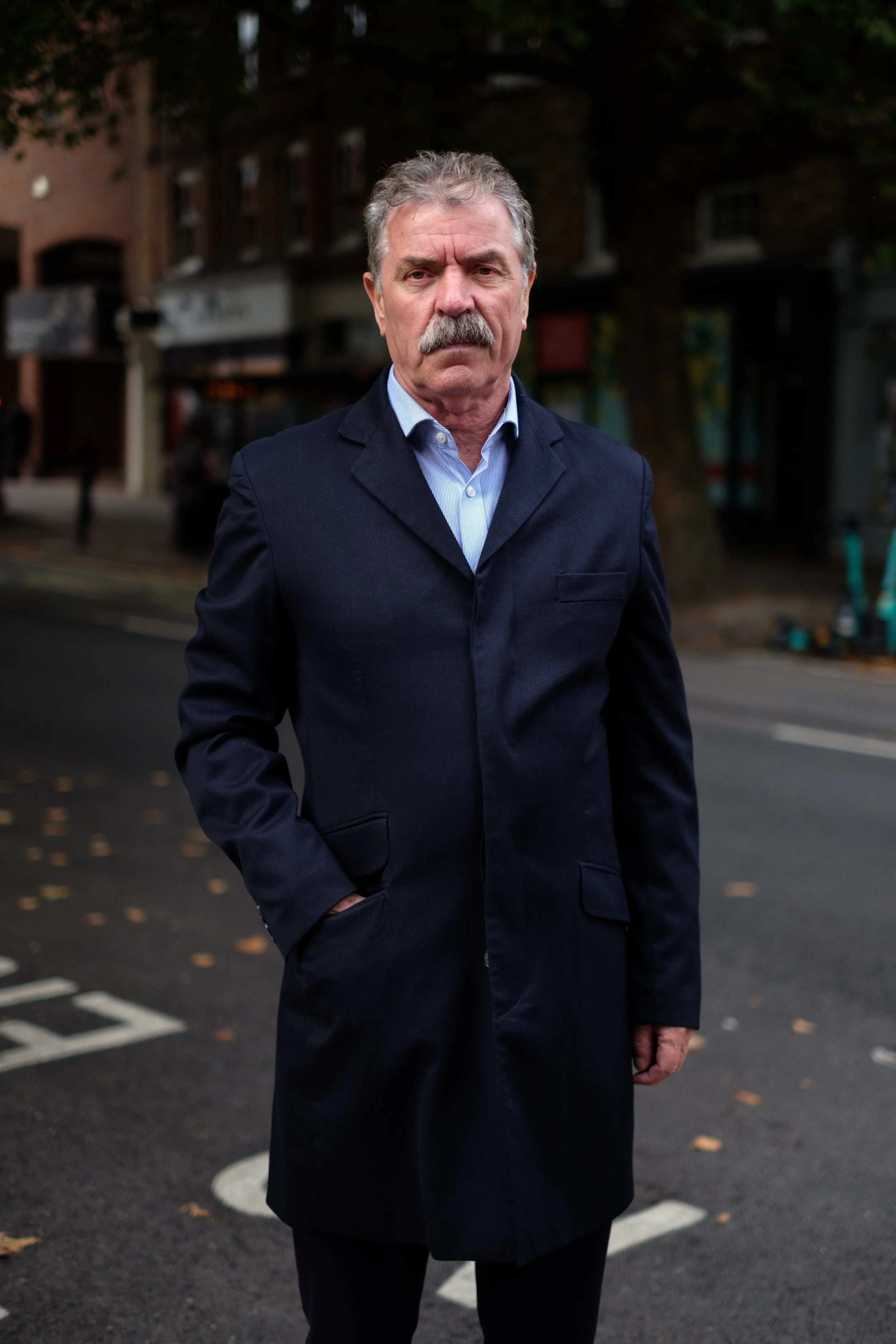

Tony Maher

Tony Maher started shaving when he was 9. There was a TB epidemic in Ireland in the 1940s, and many people in Tony's village of Monasterevin in County Kildare succumbed to the disease. Tony's mum had the job of preparing the dead for their coffins, and Tony would help his mum by shaving the faces of the deceased.

There was only one doctor in the area, and when babies were born, Tony's mum would often act as a midwife, and, again, Tony would help.

9-year-old Tony would be handed a brand new slippery baby, and it was his job to wash it. He'd then have to wrap it tightly in a long piece of cloth after putting a penny over its navel to stop its belly button from sticking out. Tony remembers how cumbersome the nappies were - great big squares of material that you'd have to fold into a triangle to make the nappy, which you'd attach with a giant safety pin.

Tony was good with his hands and, not knowing any different, wasn't bothered by experiencing so much life and death at such a young age. He was also the youngest of 9, so being in a big family, he grew up quickly. His parents had 67 grandchildren.

When he was 13, he got a job at the butcher shop. There were no refrigerators in the village back then, so the butcher would slaughter just one animal and sell it all in a day. 'From field to plate', Tony called it. They would kill the cattle and the pigs the old-fashioned way - with a hammer. This was often Tony's job. It never bothered him as being a country boy; he was used to killing rabbits and hares for the pot.

One of the reasons that a boy as young as Tony was given so much responsibility was that most young adults had left and moved to the UK. The exodus of young adults meant the town was mainly inhabited by young kids and older people. It was no big deal to see a 12 or 13-year-old working behind the bar of the village pub pouring Guinness. (The only drink on offer apart from spirits) Tony said the Guinness was different in those days, 'It was much stickier.' He said that if you let the froth run down the sides of the glass and onto the bar, the glass would get stuck once it dried out. He added that if you had a skinful, your lips would be stuck together in the morning, and you'd have the most terrible thirst.

He also said that the pubs would keep the pint glasses warm on a special shelf and doesn't really understand why they sell Guinness cold nowadays.

Tony was never that much of a drinker. When he was young, he didn't care about drink or cigarettes but loved to dance and would often walk 4 hours to Newbridge for a dance. If the dance ended late, he'd often meet his dad going out to work on the way back.

When Tony was around 15, he got a job at the general store. It sold groceries, hardware, animal feed - everything.

Once a week, someone from the store would go to the railway station with a horse and dray to collect tea chests full of provisions. Sacks of sugar, tea, and whole sides of bacon wrapped in hessian etc. This would be taken back to the shop, and then the staff would divide it, weigh it, and wrap it in brown paper and string.

Tony was one of the 6 boys working there. Everyone in the area was poor, but some old ladies who came into the shop were clearly destitute. They'd order a half ounce of tea which is a pitiful amount, and ask if there were any scraps from the bacon slicer.

Tony often slipped a bit more tea or a slice of bacon into their bags. Unfortunately, after a while, the ladies insisted on only being served by Tony, which led the boss to guess why and he sacked him. Tony never regretted getting sacked. He said that if he hadn't, he might still be working in that store now and would never have come to England.

Tony said that as you reached your late teens in the village, It was expected that you'd eventually leave. "I used to dream about life away from home - I had visions of these wonderful places where the sun was always shining. In a way, I was preparing to leave right from the start."

Just before his 18th birthday, Tony and a friend got the bus to North Wall in Dublin and then the boat to Holyhead.

Having previously worked as a butcher, Tony got work in an abattoir in Coventry. The slaughtering process was very different to back home. The animals were stunned before being killed; it was much more of a production line.

After work, Tony went drinking in an Irish pub,' The Hen and Chickens' in Keresley, on the outskirts of Coventry. He got chatting with some other Irish people in the pub, and when he told them what he was earning, they said, 'That's ridiculous, come out and work with us on the buildings where you'll get a proper wage.'

Tony said that these were wonderful times. It was 1955, and the whole place was a hive of activity, with everything being rebuilt after the war. They were rebuilding Coventry Cathedral at the time he was there.

There weren't many machines - everything was done with the pick and shovel - it was hard work, "But we were young and strong. We were natural builders because we came from the countryside and were good with our hands and were well capable of getting the work done."

Tony got paid in cash each week - sometimes in a brown envelope and sometimes just a handful of money. When it came to somewhere to eat, drink or stay, Tony said that the Irish people who'd been there a while would always point you in the right direction. There were Irish dances every weekend, which Tony loved. He met girls who were all Irish and mainly nurses.

Tony told me that being a nurse was a natural vocation for an Irish girl back then. This stemmed from their upbringing in the villages in Ireland, where people looked after each other, and everyone came from large families where everyone mucked in. Tony said he knew everyone within a 3-mile radius of his family home in Ireland. People always kept an eye out for each other - even the recluses. Tony said that if you noticed no smoke coming from their chimneys, you knew something was wrong with them and would go to help.

He said England was also different back then. It always felt safe in England. If you missed the last train, you could sleep the night on a bench in the station and not be bothered.

Tony had 2 brothers living in Harlow in Essex. His mum and dad had come from Ireland to England for a holiday and stayed with their sons. Tony's mum wanted a family get-together and sent the brothers on their motorbike with a sidecar on a mission to Coventry to go and get Tony.

Unbeknownst to them, Tony had a routine, he'd get paid on a Friday and then head off out of Coventry for the weekend on "a spree" with his mates. He didn't need much money to have a great time and often would have a bit left over for 'a cure' in the pub on a Monday morning.

The brothers arrived in Coventry, only for the landlady to tell them they'd just missed him. She was a friendly woman and let them stay in Tony's room until he got back, which they did as they wouldn't dare return to their mum without him. Sure enough, Tony appeared on Monday feeling rough. He was squeezed into the sidecar with his brother, and they headed back down south.

Once in Harlow, Tony decided to stay. It was a new town and growing fast, so there was plenty of work for builders like Tony. There was a big Irish community in Harlow back then. Enough for Tony to form a Gaelic football team. Tony loved sports but never had time for them as a kid, as he was always busy working.

At a church dance, Tony met Sheila.

Sheila is a Northerner. Her dad was a miner and died when she was three. Sheila's mum had moved to Harlow to get work and had settled there with her 4 daughters.

Tony and Sheila married in 1959. They have 6 kids, 12 grandkids and 5 great-grandkids.

They have travelled all over England together on holidays. Tony joked that he's seen more of England than Ireland. Every time he went home, he'd visit relatives and sit around their houses, so he never got to see much of the country.

Tony and Sheila Started off in a maisonette, then got a 3 bed, then a 5 bed, then a bungalow. Now Tony lives in a small house with a beautiful garden. Sheila doesn't live with Tony anymore.

About 10 years ago, when she was 77, Sheila was diagnosed with dementia. At first, Tony looked after her, but as her condition worsened, he couldn't cope as she was becoming a danger to herself. She now lives in a nearby care home.

Sheila never smoked, never drank and always had a terrific brain. Tony finds this hard to deal with, especially when he visits her and she doesn't always recognise him. He told me they call it 'The long goodbye' - "We had so many lovely years together, and it's very sad, but at least I know she's safe now. Apart from what Sheila and I have been through over the last couple of years, I've had a bit of a charmed life, to be honest."

Tony is 85 now, and his Gaelic football days are long over. The rest of his football team are 'All up the cemetery now' and thinks he might be 'The last Irishman standing' in Harlow.

"I was up the town the other day, and I said to a fella, 'There's no fun in getting old.' The fella replied, 'there is one good thing about it - it doesn't last long.'"

Margot

A few years ago, Margot was on a bus that was involved in a crash. Ever since then, she has had back problems.

She was born in Dublin 93 years ago and was waiting for a bus to take her to the chemist when I took this shot.

She told me that when she was younger, she travelled all over the world. She's been to Russia, Canada, Australia, and many other countries. She said that she's 'travelled up mountains and into deserts.’

She came to England when she married an English pilot. He passed away years ago when he was just 59.

Margot now lives on the South Coast but doesn't like it much, and if she were a bit younger, she'd go back to Dublin.

I asked Margot if being married to a pilot explained why she travelled so much.

She shook her head and said it was because her father bred racehorses. Her family would travel everywhere because of his work. She said her dad was on first-name terms with the Queen, who was a huge horse racing fan.

I asked Margot if she ever rode horses. She said she was riding when she was five years old and would still be doing so now if it were not for her bad back.

Justin

Justin was born in Wexford in Ireland. There was no work when he was young so like thousands of others, he emigrated. Justin ended up in Balham in South London where he’s lived for 35 years.

He worked at a nurse at St James’s Hospital (since demolished) and then in King George’s in Tooting.

A while ago, he visited Australia where he discovered he had lots of relatives that he previously didn’t know existed. They’d all emigrated from Ireland too, but years before and also looking for work. Justin visited some of their graves in Sydney and he said it was quite a moving experience seeing his relatives buried on the other side of the world from Ireland.

Justin is retired now. He’s 83 in May. He’s got 2 sons and a daughter but is no longer married. He divorced his wife when he discovered that ‘she looked the other way’

Phyllida

Donald and Phyllida at their Home in Balham, SW London.

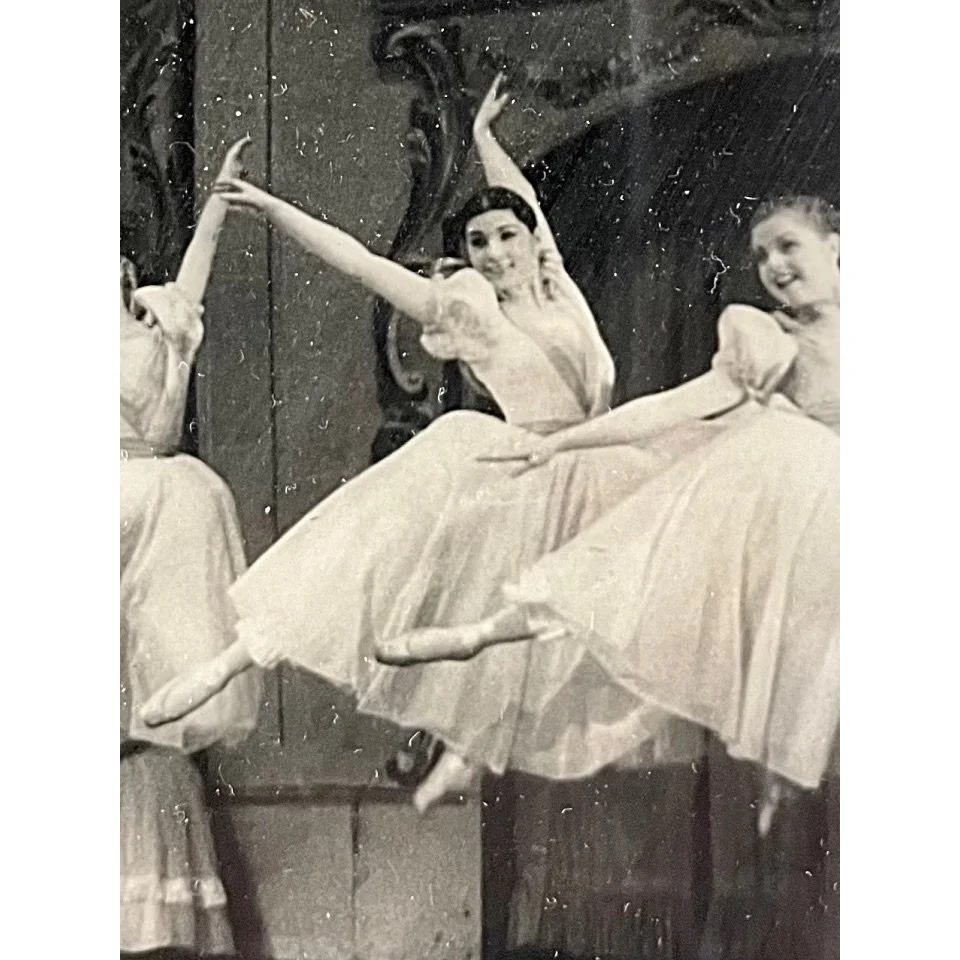

Phyllida is originally from Dublin. She came to London at just 15 to study ballet. After three years, her teacher, Anna Ivanova, was invited to put on Swan Lake and Giselle for the Cuban National Ballet and 19-year-old Phyllida was asked to join the company. Phyllida agreed and travelled to Cuba. She performed all over South America, which she told me was' such fun' for a young girl.

The company got into financial difficulties in Bueno Aires. Juan Perón, the then president of Argentina and a ballet fan, paid off their debts and lent them his yacht, 'The Evita,' to get them all back to Cuba.

Phyllida and Donald met at The Royal Festival Hall which often had ballet performances in the 60s.

Phyllida returned to London, and at an audition at the Royal Festival Hall, she met Donald, who was already an established dancer there. She told me that there's quite a hierarchy in ballet, and the other dancers didn't talk much to the new girl. Perhaps because he was a New Zealander, Donald was much more friendly, and they have been a couple ever since. They married after three months and had a working honeymoon in Monaco after dancing for Princess Grace.

Upon returning to London, they rented a tiny flat in Pimlico above a shop. The mould was so bad that mushrooms would grow in the shared bathroom, but the rent was just £2 per week.

They then moved to a flat above Clapham South Tube, which they loved as it had its own bathroom and central heating. Donald told me that he never tired of looking out at night and seeing "The strings of lights from the car headlamps glimmering across Clapham Common."

They bought their current house in Balham in 1971. The couple love Balham, "It has everything, 13 Churches, a Mosque, an Indian Temple, and so many wonderful charity shops". They have 2 daughters. One was a dancer and now teaches dance. The other worked as an actress in the theatre and is now a director.

After having her babies, Phyllida gave up dancing on stage. However, she did perform one more time. She went to Oxford with her newborn baby to watch Donald dance. One of the ballerinas didn't show up, so Phyllida's daughter was put into a drawer that doubled as a makeshift cot. While the landlady kept an eye on the baby, Phyllida had one last dance on stage with Donald. RIP Donald 2022.

Arthur

Arthur was born in 1937 in County Laois. His dad was a farm labourer, and the family of 5 lived in a tiny thatched cottage.

When Arthur was 12, his dad went into hospital for an operation and nearly died. They gave him an hour to live but somehow, he recovered. Going back to work was out of the question, so Arthur left school and worked the fields to earn money for the family. He'd plough all day with 2 horses, and the farmer would pay him £2 per week with dinner and supper.

When Arthur reached 18, he borrowed a £5 note. The banknote was a "Huge snow white piece of paper." He used it to buy the train fare to Dublin, the boat fare across the Irish Sea, and three weeks' rent for digs in England. He still had some change.

It was 1956 when Arthur got boarded the SS Princess Maud in Dublin. After it had set sail, he went upstairs and looked out the window; he couldn't believe that he was surrounded by the sea. (He'd never seen the ocean before) He'd thought that the trip would be like crossing a river and said that if he had known that the ship went out to sea, he would never have left Ireland.

In England, he worked on the construction of the High Marnham Power Station in Nottingham.

After a few months, Arthur decided to go to London. He stayed with a cousin near the Oval Cricket ground in South London.

He got work as a landscape gardener and did this for 52 years. "It was the first job I got in London and the last job I got in London."

Arthur's first wife, Margaret, was from Tipperary. They met in The Galtymore dancehall in Cricklewood. They had a daughter, Caroline. Sadly, Margaret passed away at just 33. They had been married for 10 years.

A few years later, Arthur was back in Galtymore dancehall when he met his second wife, Mary. They were married for 46 years until she passed away aged 83.

Arthur never regretted coming to England. "If I hadn't come, I'd still be back in Ireland eating grass."

He loved his job, but eventually, they said, "Arthur, you've gone past your sell-by date., it’s time to put down your shovel” He retired at 72.

He has bad knees from all those years digging, "I worked hard, but I don't regret it. I've had a great life - I just wish I still had my two girls with me.”

Michael

Michael’s living room has an old photo of his dad in army uniform. Michael never got to meet him in person because a month before Michael was born, he died of pleurisy.

This was 1939 in Ballymote, County Sligo.

Michael did well at school. He got his leavers certificate a year early and was allowed to leave at 14.

The priest came around and said, “Michael, you are going to college.”

Michael said, ‘No way,’ The priest looked at his mum and was surprised when she said, “It’s up to Michael what he does with his life.”

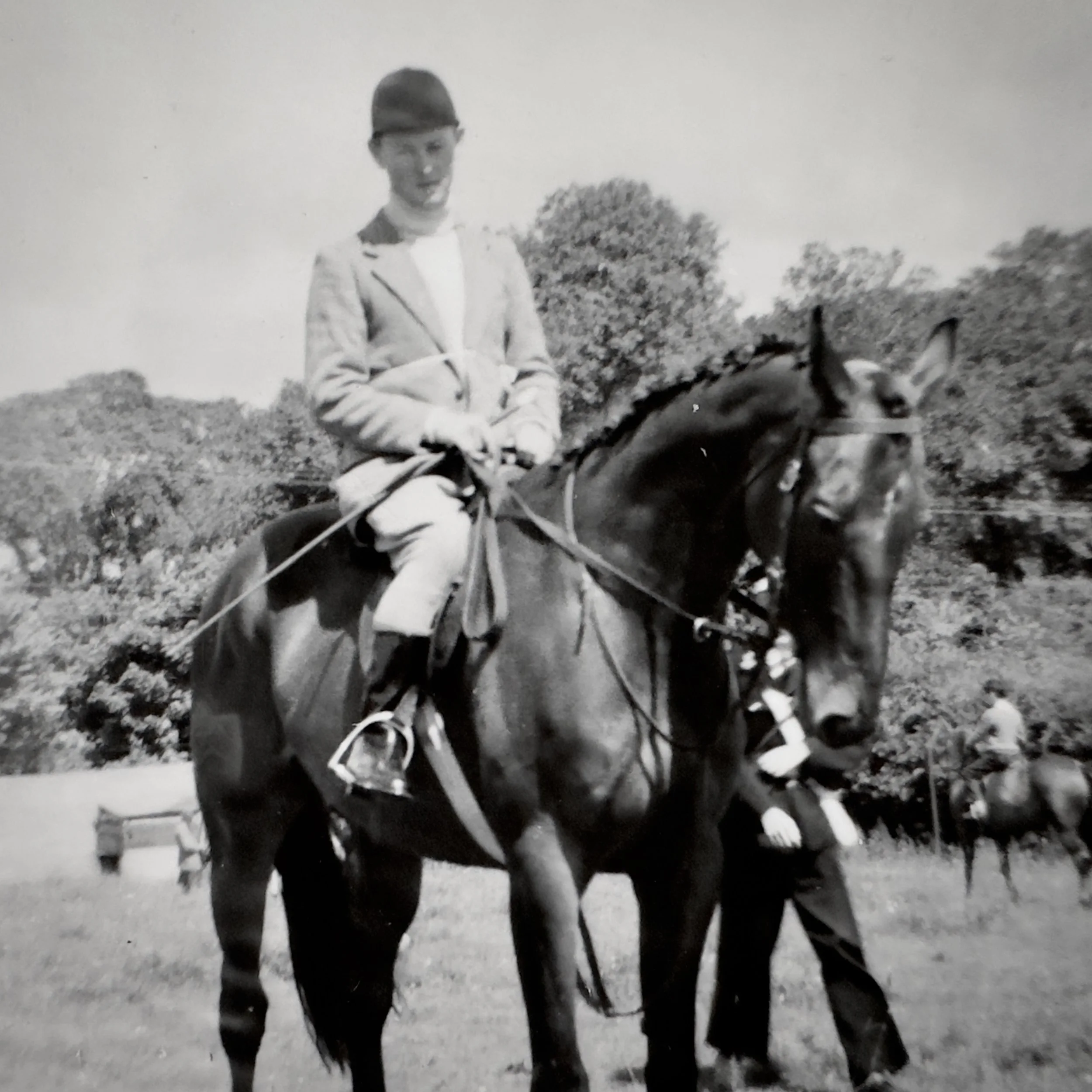

So Michael left school to pursue his dream of becoming a jockey.

He’d been pony racing since he was 6. After mass on a Sunday, everyone would turn up with their ponies and race.

Many famous jockeys, including the racing legend Sir Tony McCoy, started their career in pony racing.

During the week, Michael was paid to look after the horses and the stables. The money was terrible, but Michael lived for the races. He was doing well, and after winning one, he was approached by a man from Northern Ireland asking if he fancied racing in Enniskillen. Michael asked about the pay, and the man replied, “It depends if you do as you are told - we will want you to win some races and lose others.”

Times were hard back then, and Michael had to support his widowed mum, so he agreed and started his career as a ‘Flapper racer.’

Flapping is horse racing that isn’t run under Jockey Club rules. Once a horse or jockey participates in a flapping meeting, they are no longer eligible to participate in ‘proper’ racing.

Unfortunately, not long after, a man from the Irish turf club took Michael’s photo, and he was, in Michael’s words, “Done for like a kipper.”

His hopes of one day becoming a professional jockey were over, so he came to England and got work as a decorator in Wimbledon.

Not long after, he met Noreen at the Hammersmith Palais. She was a seamstress, and they got married and had four kids.

Noreen’s uncle then got Michael a security job at the ’Town Terminal’ in Kensington. When Heathrow first opened, they thought that only the wealthy would get flights and would be dropped off by chauffeurs or taxis. They didn’t allow for the huge number of passengers wanting to fly and the growth in car ownership.

To lessen congestion, a facility was built in Kensington where passengers checked in and dropped off their luggage before being transported on buses to the airport itself. Michael worked there until the mid-70s, when the Piccadilly Line was extended to Heathrow, making the Town Terminal obsolete.

Michael then went for a job interview at Victoria and Albert Museum. Having worked in airport security, Michael had an excellent CV, and they gave him the job on the spot.

He loved working in the museum. He loved walking around the empty galleries after everyone had gone home.

Because the museum had many functions, he also met many dignitaries and famous people.

He met Princess Diana, whose lady-in-waiting handed him some flowers to look after while she was at a function. As she left, the Princess turned and thanked Michael in person.

On another occasion, Prince Michael of Kent was visiting the museum. Michael was told to direct the royal car to the dedicated parking space. When the Prince arrived, Michael told the chauffeur to follow him as he walked to the space. The Prince called from the car and told Michael to hop in as they drove to the parking area. As Michael passed his boss in the Royal car, he waved regally.

Later his boss joked, “Trust you, Reynolds, to get your Sligo arse into a royal car.”

Michael could have retired at 60, but the bosses called him in and said we like having you around, so he stayed until he was 65.

Looking back on his life and all the experiences and opportunities that he has had, Michael is ‘over the moon’ that he came to England.

Michael around 16 years old.

Moira Dempsey

Moira has always loved music - especially Irish music. One of her first memories is listening to the radio in their rural house in County Monaghan. Her family lived in a remote place along a narrow lane. On one occasion, they had to call out the doctor, and he scratched his car en route and said he'd never come back to such an out-of-the-way place again.

Her dad was a talented builder. He was a gifted stonemason and a master carpenter. He was a quiet man, but when he got drunk, he would fly into a rage and abuse Moira's mum. Moira remembers being scared of an evening waiting for him to come home from the pub. Just talking about it still upsets her today - over 60 years later.

Moira's mum was called Bridget, but everyone knew her as "Cissie." She had a brilliant sense of humour, was a good singer and could have done anything with her life, but she was stuck in a marriage marred by her husband's alcoholism and abuse.

Her dad kept drinking all his wages, so Cissie got a job in the factory to feed the kids.

She went to see the priest for help, but he said marriage was sacred and, 'You've made your bed, and you have to lay in it."

Cissie put up with the abuse for 20 years, but in the end, they made their escape. One day, when Moira's dad was at work, they packed their bags and came to England. Cissie only had £15 to her name, but she had to get away. Cissie, Moira and one of her brothers made the trip - her other brother was away on a course and would come over later.

They went to stay with a friend in Surbiton for the first night and then in a B&B.

Cissie got a job in a launderette. 13-year-old Moira lied about her age and worked there for six weeks with her mum. This was 1962 when it was easy to get a job in England. It was hard work, and Moira remembers struggling to feed the heavy washing into the big rollers.

They'd come to England in July, and Moira went to the local convent school when the school holidays ended. It was full of second-generation Irish and Italian kids. They were all fascinated by Moira's strong Irish accent - they kept asking her to talk so they could hear it. This actually had the effect of making her a quiet girl.

Moira said the other girls at the school were lovely. Nobody in England knew about her dad's drinking problem. It felt like all the shame Moira had suffered back in Ireland from having an alcoholic father had been left there. Thanks to the bravery of her mum, it was a new start.

Cissie did loads of jobs to put food on the table for her kids. She ended up working as a cook in the BHS canteen. They moved around quite a bit but eventually ended up living in New Malden.

Moira remembers missing Ireland so much in those early days. She had to leave so much behind, including all her friends. She'd often dream of them and then wake up and realise that she couldn't just pop down the lane to see them, as she was in another country.

She loves an old Irish folk song, 'Spancil Hill,' (Sung by Christy Moore in the 70s) because it encapsulates how she felt back then.

Last night as I lay dreaming of pleasant days gone by

My mind being bent on rambling, to Ireland I did fly

I stepped on board a vision, and followed with a will

and shortly came to anchor at the cross of Spancil Hill.

Cissie always remained concerned about her husband. She kept in contact with him and said he could come to England if he wanted. Whenever he had enough money to come, he would spend it all, 'going out on a spree.' He never made it to England.

When he died at 72, Cissie wasn't entitled to a widow's pension. Ironically, he was paid a 'desertion payment' when he retired.

After school, Moira did a couple of jobs before working for the building society Abbey National (Now Santander). She worked her way up to a management position and stayed with the company for nearly 40 years.

She met Joe when she was 30. She'd had a few boyfriends before, but nothing serious.

They met at The Hibernian Dancehall in Fulham in 1981. Moira had spotted Joe on a few previous occasions and thought he looked handsome with his dark hair and beard. For obvious reasons, Moira always had it in her mind to see what a man was like when he'd been drinking before she decided to take it any further. So it was handy that when Joe plucked up the courage to ask Moira, "Can you handle a dance?" he'd clearly had a few too many. Moira could immediately see that he was a gentleman and still polite when he had a drink.

Joe is from County Laois and came to England in the 70s to work as a welder. Cissie loved Joe and was delighted that her daughter had found such a kind man to spend her life with. Cissie passed away when she was 85 - she never went back to live in Ireland. Moira's brothers, who all live close to Moira, had kids, and Cissie didn't want to move away from her grandkids.

Moira and Joe have been happily married for almost 40 years. Over the years, Joe has lost his hair and most of his beard, but Moira hasn't lost her love of him or Irish music. She's been doing Irish Set dancing since the 1990s. At first, she went to lessons, and when the teacher returned to Ireland, Moira became the group teacher. She taught Set and Ceili dancing for thirty years and ran many Ceilies, which raised money for charities. She finds it very rewarding and has met some lovely people.

Moira confided that dancing has been the 'Saviour of my life.' If she is ever worried or upset, she forgets everything when dancing. Moira and Joe visit Ireland every year to visit relations and go to music and dance festivals. They meet up with lots of people whom they know from the dance scene. Moira loves this because she feels like she belongs when she's doing her Set dancing in Ireland.

However, that feeling of belonging isn't something that she always feels when she's in Ireland.

She loves her time there and seeing her relatives, but it just isn't home anymore.

Joe and Moira have thought about going back to Ireland to live but feel that this is unlikely now. They have made a life for themselves in England. Moira added that she will always be Irish and will always love Ireland, "I can accept being a foreigner in England, but I couldn't be one in Ireland."

Theresa

Theresa was born in Athlone on the River Shannon in Central Ireland.

Her family owned a shop/pub called Galligan's. Back then, in Ireland, it was common for the local grocers to have a bar and a few tables and chairs for drinkers.

Times were hard, so her mum and siblings moved upstairs and rented out the shop below. Her dad had already moved to Rugby in England to work on the busses. Theresa still remembers the registered letter arriving every Friday with the money that her dad sent back.

Her mum was a dressmaker and did alterations, and they also took in lodgers, so they got an extra few Punts.

Theresa told me that she had a lovely childhood, “The money wasn't there, but I think we were a lot happier than people are nowadays.”

When she was 17, she got pregnant. Theresa was way too scared to tell her mum, so she came to England. She told everyone that she was just going on holiday, but had got a job in a pub that she saw advertised in an Irish newspaper. She just had to get away. The shame of being unmarried and pregnant in Ireland in the 1960s was too much.

The bar where Theresa worked was in Tottenham, and she lived in a room above. The hours were long in the busy London pub. Theresa worked until 1.30 am and then had to be up for mass at the local church at 7 am.

The father of the child that Theresa was carrying was called Tommy, and he was a soldier. She'd met him through his brother, who used to drink in the family shop/pub in Athlone.

When she wrote to Tommy to say she was pregnant, he deserted the army and came to England to be with her.

They managed to get their own place in Cricklewood in North London, and both got jobs in the McVities biscuit factory in Harlesden. The factory is still there - the largest biscuit factory in Europe.

One night, they went for a drink with Theresa's brother and one of his friends who worked in the local Job Centre. She said to Theresa, "What's a girl like you doing working in a biscuit factory? Come and see me at work tomorrow, and I will sort you out." Theresa went the next day, and the friend got her a job doing accounts. This was much easier work for Theresa as she'd always had an aptitude for figures. Even now, she can still add up the cost of her shopping in her head as she goes around the supermarket.

She had a baby boy. Although he wasn't planned, Theresa thinks that he was one of the best things to happen to her. He's 55, lives in West London, and deals in antiques. He and Theresa often meet up in London for lunch.

When the baby was eight months old, Theresa finally plucked up the courage to write to her mum and tell her the truth. She sent photos of the baby along with the letter.

At first, Theresa didn't hear back, but her mum's neighbour saw that her mum had put the baby photo on the kitchen cabinet and told her, "You have to write to her; it's your grandson," A few days later, Theresa got a letter saying, 'come home.'

Theresa married Tommy. She faked her dad's signature because, in Ireland in the 60s, a girl under 21 had to have her father's consent to marry. At the time, her dad was still working in Rugby, but she didn't get in contact - there was no way she was going to tell him that she had an unplanned pregnancy.

When they got back to Ireland, Tommy, who had deserted, had to hand himself into the military police. He was court-martialled and got a 6-month term in 'The Glasshouse' detention camp in The Curragh.

The minister of defence lived in the same town as Theresa. So she went to his office and told them she had a baby and couldn't survive without Tommy's wage. Her pleading worked because his sentence was reduced to 6 weeks. Upon leaving the detention camp, Tommy got work as an engineer. The couple got a cottage and had two more sons.

Tommy was always a very jealous man. At first, this wasn't too bad, but gradually, this got worse, and he started to get violent. He would never let Theresa out of his sight and was suspicious of her every move. Tommy would get abusive even if Theresa visited a female neighbour. The constant, 'Who are you talking to?' made life unbearable, and after 12 years of this, she just walked out the door and went back to England. Tommy was fine with the kids, so she left them with him until she settled.

She got a room in Balham in South West London and got a job in the nearby Prince of Wales Pub. Once she had found a place to live, she bought her kids over.

A few years later, she was working in a cafe in nearby Battersea. She got chatting with a customer who often came in for breakfast. His name was Hersey, and he was a landscape gardener. They eventually became a couple, got married, and had two kids together. Theresa isn't sure why she married Hersey. Looking back, she was 38 at the time and thinks she probably did it just to get a bit of security.

Unfortunately, he also became violent. He had a real Jekyll and Hyde personality. He could be very loving and kind but could quickly fly into a rage. He once threw Theresa over the bannisters. Again, Theresa left. She told me that she thinks that if she had stayed, there was a chance he would have killed her.

Years later, Hersey was on his deathbed, and he got in touch with Theresa. She went to see him, and he said, "It wasn't all bad, was it?" Theresa replied, "We had some good times, and we had some lovely kids. You were always a fighter, so fight this." It was the last thing she said to him because he died shortly after.

Theresa was given a new flat in Stockwell by a housing charity for women who have suffered domestic violence. She said she was lucky to get a flat because usually, people just get rooms. Perhaps because she was finally in a safe place with time to reflect, she became depressed. Theresa had been through a lot over the years, and sitting alone with her thoughts, she started to drink. At first, it was just a glass or two of wine in front of the telly. But this built up until she was getting through 3 bottles a day, along with several vodkas. She said the funny thing was that she could drink all that and go out, and people wouldn't have a clue.

One day, she realised that she had to stop. So she went to an AA meeting in nearby Brixton. When Theresa plucked up the courage to walk through the door, she was shocked to discover that the person running the group was someone she knew from back in Ireland, who she hadn't seen for 40 years. Once she got over the embarrassment, she did a few AA meetings and something inside her clicked, and Theresa stopped drinking. At first, the sickness caused by her body reacting to no alcohol was unbearable, but eventually, she got better and has never touched a drop since.

Theresa loves her flat and told me that she has great neighbours, which is the most important thing to her. Her postman is one in a million - he always asks how she is and helps carry her shopping. Her neighbours will take her rubbish down to the bins, and she lives close to a Brazilian cafe where she has made many friends. Her group includes women from Norway, Germany, Holland, Jamaica and a Londoner.

Theresa also has a new partner. 72-year-old Sullivan from Cork. They don't live together and are more good friends than anything. He lives in Wandsworth, brings her the Irish papers every Sunday, and does any repairs needed around her flat. Theresa likes it that way, "I'm too set in my ways to live romantically with another man."

However, Theresa does live with another man, a builder who is her lodger. He's lived in the spare room for 11 years, but Theresa told me you'd hardly know he was there. He gets up early to go to work and always leaves his room and the bathroom spotless. It's reassuring for her to have someone there. Theresa has balance issues and has had a few nasty falls, so has been advised not to live alone. She and the lodger share the shopping bills. She does a big shop at Asda every week but will also go to Iceland when it's 10% off on pensioners day.

She is still in touch with her first husband, Tommy. He's in a care home now. They get on well, and she doesn't hold any grudges. She told me, "I'm 75 now and can honestly say I'm happier now than I have ever been."

Theresa also loves Irish dancing and Irish music. She often goes on dancing holidays and cruises and has been all over Europe on dance-related trips.

Theresa's biggest passion is reading. She gets through 2-3 books a week. As she showed me the stack of books by her bed, waiting to be read, she said with a grin, "I used to be an alcoholic, but now I'm a 'bookaholic.'"

Mary Coughlan

Mary Coughlan is 78. She was born in Cork but has lived in Waterloo in central London for the last 60 years. She said it was tough at first back in the '50s, but in the '60s, everyone started to earn more money, and life in London' 'got good.'

Mary was sitting on a bench outside a pub when I took this shot. She wasn't drinking. She's just finished a Mcdonalds' apple pie which she says is a treat she sometimes has before getting the bus home.

Mary never married. She loved travelling too much. She does have a long-term friend, though. Wilfred. He's German and 'is a very kind man.' They met on a bus in Regent Street and have been together for years. He keeps the flat tidy, and she told me that he will be back there now cooking her some fish for tea as it's Friday.

I asked her what her family back in Ireland thought about her not getting married. She said her 'mammy' was fine about it after a while because she could see that Mary was happy.

When she first came to England, Mary told me that her mum would phone her from Cork twice a week to check that she was okay and eating properly. This carried on until just four years ago when her mum passed away aged 104 and Mary was 74. 'She is dearly missed,' said Mary.

Tom Ryan

Tom Ryan was born on a farm in Tipperary in 1937.

He might still be there now if it weren't for a phone call he got from a friend in 1961. His friend had already come to England and told Tom he should do the same. Tom can't remember why he came. He thinks it was just because he was young and adventurous. "When you are young, nothing is too hot or heavy, but when you are old, everything is too hot and heavy." A week later, Tom started working behind the bar in a vast South London pub, The Falcon in Clapham Junction. Arriving in London was a big culture shock for Tom. Before then, the only pub he'd ever seen was a small area set aside for drinkers in the general store in his village back home.

Despite working in a pub, Tom is a teetotaller. The 'Pioneer’ movement was introduced to Ireland in 1889. It encouraged Irish kids to vow never to drink and when Tom was a teenager he took ‘The Pledge.’ Tom said, "It's a promise but not an oath; if you break it, you are not committing a sin." Nevertheless, Tom has never touched alcohol. He struggled at first to understand the customers, "I didn't understand their Cockney accents. But to be honest, they had less chance of understanding me." The other bar staff were friendly and showed him the ropes. The first place he visited was the Granada Cinema in Clapham Junction, where he went to see the movie, 'The Guns of Navarone.' Tom never got homesick because he'd go back to Tipperary at least 3 times a year.

A guy Tom knew in the pub got him a job in the tarmacking trade. Tom never liked working in the pub. He didn't like all the noise and the late hours. He much preferred being outside, and tarmacking gave him much more freedom. His first job was tarmacking the paths in the nearby Battersea park. He told me you started and finished early, and the more work done by 'dinner time' (midday), the better. He added that you have to work hard and you have to work fast because the tarmac sets.

Most of his co-workers were English. Tom enjoyed working with them and said they were nice blokes. There was always the odd joke, especially when England played Ireland at rugby - but there's always banter around building work.

Tom believes that when you are new to a country, you are "Fashioned by the people you meet; the people you get to know influence you and set your path." One of those people was a friend he knew from Cork who was a keen runner. He said that Tom should come to his athletics club to watch him run in a race. Tom, who was around 30 then, always enjoyed watching athletics on the telly, so decided to go.

It was a two-mile race, and just before it started, Tom, who was a heavy smoker at the time, put his cigarette out and decided to have a go himself. Even though it was the first time he'd ever run competitively, Tom nearly won and finished considerably quicker than his mate.

This got Tom into running and when he wasn’t out laying tarmac, he was out training. Someone told him to give up cigarettes because maybe, he could be good. So one New-Years Eve at 5 minutes to midnight, Tom gave up smoking and has never touched a cigarette since. He joined a running club, North London Athletic in Hampstead. He mainly ran cross-country and trained on Clapham Common, close to his home in Battersea.

Tom started to compete and would often win. He also ran back in Ireland, and would win there too.

He won the all-Ireland 5-mile trek championship and the 15-mile road race.

He raced in France with Hercules Running Club in Wimbledon.

Tom started running late in life, and it’s hard not to wonder what would have happened if he’s started in his early twenties rather than his thirties. He’d race against athletes that he used to watch on the telly when he was younger and would often beat them. Even when he was 40 years old, he could run 5K in just 17 minutes.

In his 50s, he ran a half marathon in 1h 13m and came 2nd in the national championships for the over 50s.

Having tarmacked countless car parks, roads, school playgrounds and even Brands Hatch racing circuit, Tom retired at 70. After retiring, Tom volunteered to help maintain the gardens at the Archbishop's House at Westminster Cathedral. He'd water the plants, care for the patio and get rid of the weeds that would grow around the Cathedral itself. Tom was on first-name terms with Cardinal Murphy-O'Connor, the then Archbishop of Westminster. One day, he and a mate were told to get 'suited and booted' before coming in to volunteer. That day, the Queen paid the Archbishop a visit, and Tom and his mate met her. "We didn't have to do anything, just stand there and look smart." The Queen walked around and said hello to them but didn't say anything else, but Tom said Prince Phillip was very chatty.

Tom's 85 now, and his running days are over. He recently tripped on a loose manhole cover while running for a bus and tore a hamstring. He also suffers from bad feet and regularly has to see a podiatrist. I asked him if he ever did all that stretching like the joggers one sees on the streets today. He said nobody ever did back then, "The only stretch I've ever done is reaching for the soap in the post-run bath."

John never married. It's just something that never happened. He went out with a few girls for about a year or so. He never fell out with them, but long-term relationships just didn't happen. Tom told me, "Things you don't do in life, you regret. But when you think about it, what's the point of regret? It hasn't happened, and that's the end of it." He's philosophical about living alone. He said with a grin that there is a plus side, “If you want to go to the toilet in a hurry - it's always ready for you."

Throughout his whole time in England, Tom has always lived in Battersea. His current home is less than a 10-minute walk from the Falcon pub where, 61 years ago, he first lived and worked. Tom loves all the green space close to his home. He loves the transport system in London and the fact that you can go out and buy a pint of milk at 10pm. You'd never be able to do that in the countryside around Tipperary, where he was born.

Tom said he would never go back to Ireland. "There'd be no point. Now that I am old, I’d have to live in a town - I come from the countryside, so it would be just as different as living here."

Throughout all this time, he has always stuck to The Pledge and has remained a teetotaller. He said the trouble with drink is simple, "One pint isn't enough, two pints is too much, and three isn't half enough - that's how it works."

Alan Hopkins

Alan Hopkins was born in Wicklow in 1940. His father ran a grocery store in the town, set up by his Great-great-grandfather in 1827.

The shop is still going and is run by one of Alan's nieces. It now sells toys and is the first shop in Ireland to sell Lego after the founder of the famous Danish company visited his shop while on holiday.

Alan's family are Protestant. He remembers that there was quite a divide between the Catholics and Protestants in Wicklow, and they never really mixed.

Alan has 2 sisters and a brother - his eldest sister is 96 and lives in America. She was a GI Bride, having met an American soldier in WWII when she was in the service.

Alan's other siblings are 93 and 89 and live in Ireland.

Alan was the youngest by 7 years, his mum being 40 when he was born. She'd often tease him and say he was a mistake as she'd already sold the pram and cot, but she added that he was ‘as cute as a fox.'

Being by far the youngest of his 32 cousins wasn't easy. Everyone was always so much older and bigger than him. Being Protestant, he wasn't allowed to mix with Catholic boys, so he had quite a lonely childhood.

There were only Catholic schools in Wicklow, so Alan, aged 10, was sent off to a Protestant school outside Dublin. He didn't do well at school as he wasn't that academic, and he left at 15.

Alan's big brother was already looking after the shop, so Alan had to find his own job.

He got an apprenticeship at a garage in Dublin. He wasn't interested in cars in any shape or form and didn't enjoy the job. He doesn't like pubs or football either, which must have made it hard for him to get along with the other mechanics.

A girl he knew in the village told him she was off to Dublin to do a pattern-cutting course. Alan had always loved clothes and fashion and decided to do the same.

His parents were supportive of this decision. Alan’s parents weren't prescriptive and let him make his own decisions.

The college and the course were perfect for Alan. It was somewhere where he felt like he belonged. He completed the 2-year course in just 9 months.

He then got an apprenticeship with Mary O'Donnell. Who was a famous couturier in Ireland. Alan loved his time there but dreamed of going to London. He wanted to 'open up his life.'

Back then, Alan felt that the city of Dublin was still quite a narrow-minded place, and it was much worse in smaller places like Wicklow. Wicklow always felt like a backwater to Alan. There were only 2 newspapers, and they were tabloids. They were also heavily censored - many pages of the British press sold in Ireland were blank or had articles removed due to censorship. When TV came arrived, people could get the BBC and a different POV - but only if their house faced England and had a big enough aerial.

Alan remembers the first time he arrived in Londons' Victoria Station. He went straight into a nearby Army & Navy store and marvelled at the variety of things on offer. Compared to the shops in Wicklow, this was the most wonderful thing he'd ever seen - it was so exciting.

Back in the 60s, there was so much work available in the capital that you could leave a job on Friday and start a new one on Monday. Alan got work as a machinist in a company that made ready-to-wear couture. It wasn't long before Alan was promoted to pattern cutter.

He then began working for the couturier Fredrick Starke, who designed some of the costumes for the actress Honor Blackman in the cult tv series "The Avengers."

This was in 1966, and it was at work that he met Vanessa. She was a fashion graduate from Ravensbourne School of Art and was doing a work placement.

One night, he asked if she would like to accompany him to the ballet, and they just hit it off. They shared the same interests in cinema, theatre and culture. "We laughed at the same things and just clicked." Alan added, "You either click with people or don't, and Vanessa and I certainly did."

This was the Swinging Sixties, but Alan admitted, "We weren't that swinging - we preferred antiques and history to The Rolling Stones."

They married in 1969.

They looked for a flat and worked their way along the Northern Line until they found somewhere they could afford. The rooms were too small in Stockwell and Kennington, but they loved the greenery and vibrancy of Balham, and that's where they settled.

The couple had two kids - Sam and Alice.

In the recession of the 1980s, Alan was made redundant - he used the opportunity to turn his love of antiques into a business and rented a small stall on Portobello Road. He bought "Little bits and pieces" at auction and at the famous Bermondsey market, which opened at 6am every Friday. He'd then clean up what he bought to sell the next day in Portobello.

The trouble was that the couple loved some items so much that they couldn't bear to sell them. Since her fashion student days, Vanessa has always loved antique clothing, accessories and fabric. Over the years, they amassed quite a collection and Alan became known in Portobello for the materials he sourced.

By then, Vanessa was working in the costume department at the BBC. A costume designer who was working on a period show, asked Vanessa to get Alan to come in to meet her with some of the fabric he'd collected. When she saw it, her eyes lit up, and she bought a lot from him.

Alan and Vanessa's reputation spread around the BBC, and they began to supply the corporation with more vintage outfits and accessories.

After a while, the couple realised that what costume designers really wanted was vintage fabric, which would allow them to make authentic costumes to fit the actors perfectly.

Because of the nature of the fashion business, where there's always a rush for the new, period fabric was never kept, so it became extremely difficult to find.

The couple searched around and found people who could make reproduction period fabrics based on Alan's huge collection of antique samples. They worked with a silk mill in Norfolk that has been going for 300 years to recreate exact copies of the originals.

Alan and Vanessa set up a company - 'Hopkins Fabrics,' and the business was hugely successful. Their fabrics were used by costume designers all over the country and often in America too.

The couple have also published books on their collection in a collaboration with the School of Historical Dress.

Vanessa's love of history meant she knew how to research and write about the featured items. Alan did all the photography in a spare room of their Balham home.

Cataloguing everything that they have collected was quite an endeavour. They'd actually forgotten just how much they had acquired over the years - they found incredible things like the bonnet from the 17th century. Everyday items of clothing like this are so rare because the working classes wore their clothes until they were threadbare so they rarely survived. It's much easier to find the clothes of the wealthy.

The couple have been married for 53 years and have lived in the same Balham house for nearly 50. They still love the diversity of Balham and the mixture of cultures. They often jump onto the tube to go to the West End to enjoy theatre, restaurants and ballet.

They particularly love the cinema and often visit the nearby Clapham Picture house. They try to see a different film every week, from blockbusters to more obscure foreign subtitled films. And, of course, if there’s a period drama showing, there's the added bonus that the couple might get to see some of their own fabrics up on the silver screen.

MARY

Mary and her friend left Tipperary to start jobs as nurses at London’s Whittington Hospital.

They arrived in London about a month before the hospital job was due to start to give them time to get settled.

Mary's friend was a lot more worldly than Mary. She was a bit wild and loved going out. She said to Mary, "Let's get a job now to get money to buy clothes." So the pair got a job at a factory in Harringay that made thermometers. Mary then got a job as a barmaid in the Medina Pub in Finsbury Park, a job in a pipe factory (The type of pipe you smoke) and then a job in a brewery.

Neither girl got around to taking up the nursing jobs they came to England for. Mary's friend just wanted to have fun, and on reflection, Mary doesn't think she had any intention of becoming a nurse. She just wanted an excuse to come to England and be independent. Mary admits that she was more than happy to tag along with her friend.

If they had a 6am start at the brewery. They'd stay out dancing at The Gresham Dance Hall until 1 am and then go home and chat all night, drinking fizzy orange. They didn't bother going to bed; they'd go straight to work.

At the brewery, they'd play loud pop music all day on the tannoys, and it was Mary's job to check that the labels were straight as the beer bottles passed by on the conveyor belt. She'd often be so tired from all the dancing and chatting the night before that she'd sometimes doze off at her station. Her boss would wake her up by dropping a beer bottle into the 'reject bin' right next to her, causing it to smash loudly. It was all done in good humour, and Mary loved the job.

At another dancehall, St Olive's, she got together with Richard from County Clare. "He was tall and slim, just how I liked them" She already knew him a bit through his brothers, but after that dance, they got serious and, after a couple of years, got married. Everything was going great, and they had 2 sons. Mary got an evening job behind the bar of a local bingo hall while Richard babysat. These were good times.

They then found a lovely flat in Stoke Newington. It was a great flat but moving there was a big mistake. It was away from all their Irish friends and family, so it was just the two of them and the kids. It wasn't long before they realised they didn't have much in common, and Richard left when the kids were around 5 and 6.

Mary had to bring her boys up on her own. By then, she had a job in the office for a company that was involved in buying and selling all sorts of different things, and the bosses really helped Mary out. They gave her an oil heater to keep the flat warm and a whole load of new clothes for her and the kids. It was a tough time, but Mary managed to get by.

Twenty years passed. One night, Mary was in a pub with a group of friends. She was coming out of the ladies when she was intercepted by Pat. He was a Mayo man she knew from when she first came to England in the early sixties. She'd always liked Pat, and it transpired that he had always loved her. He thought she was 'Marriage material’ but he was too shy to ask her out even though they lived in the same rented house where Pat slept in the room directly above Mary.

They are finally a couple now. They don't live together, but see each other most days. Mary likes it that way. She wants to keep her independence.

Pat says he wishes he'd had the courage to ask Mary out back when they shared a house. After all, he often jokes, “I was sleeping on top of you every night anyway.”

Mary volunteers at an Irish lunch club in Hackney.

Theresa

Theresa loved school, and her favourite subject was maths. She remembers crying when the snowdrifts around her family farm in County Leitrim meant she couldn't walk the 4-mile journey to class. She was the eldest of 8, and unlike Theresa, her younger siblings were delighted to be missing lessons.

She left school at 14 and got a job at McGowan's, the village shop (Now a 'Spar' minimart). She worked there for a while, but when her mum had to go into hospital to get her varicose veins sorted, Theresa stayed home to look after her siblings. She did this for over a year as her mum didn't heal properly due to a piece of gauze left inside her wound from the operation.

At 16, she got a live-in job working for a vet and his wife across the border in Belleek. She helped look after their newborn baby and answered the phone in the vet's office. She got half a day off a week. She would work for four weeks straight so she could have a whole weekend at home.

On one of those weekends, some cousins who'd moved to London returned to her village on holiday and asked Theresa if she wanted to go back with them.

Her parents weren't too pleased about her just taking off, but she was 17 and wanted the adventure.

She took the boat with her cousins and stayed at her auntie's in Fulham. Within a couple of days, she had a job working in a Lyons Tea House in Victoria. Because she was good at maths, her bosses saw how quickly she added up the takings and promoted her to supervisor. She had to travel all over London to work in different branches. (There were around 200Lyons Tea Houses in those days). The size of London was a shock for Theresa, but she got used to hopping on a bus or the tube in no time.

Theresa always sent money home to her mum and dad, and when her younger siblings moved over, she made sure that they did too.

She met her husband, John McGowan, at the newly opened Hibernian club on Fulham Broadway. He was from Boyle in County Roscommon and worked behind the bar. He was also in a small band with his brother, playing Ceili and other Traditional Irish music. Theresa remembers how smart he looked in the white jackets all the bartenders had to wear.

They courted for about six years while saving to get married. They went dancing, to the cinema and visited each other's families. But sex before marriage was unthinkable in those days.

They tied the knot at Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in Fulham in 1963. After marrying, they rented a flat before buying a house in Fulham, where they lived for 20 years. Theresa still has the first piece of furniture she bought, a dressing table. She joked that it must be an antique now.

By then, John got a job for London Transport. Theresa and John tried for years to start a family. Teresa did eventually get pregnant, but she lost the baby. She couldn't go through that experience again, so the couple signed up with an adoption agency.

Around this time, Theresa was learning to swim. After a lesson, she got chatting with a woman about her situation. A few days later, the woman phoned and said she was looking after a young girl who was just about to have a baby. The girl, originally from Donegal and unmarried, wanted to put the baby up for adoption.

Theresa and John met the girl at the hospital just after she had given birth. They all got on well, and she agreed to let them have the baby. It was a private adoption which in those days was legal. (It became unlawful just a year later).

Theresa called the baby Elaine at the request of the young girl. The baby's second name is Philomena, after the lady from the swimming class that made the introduction.

Suddenly, without any notice, Theresa and John were home with a tiny 9-day-old baby. Luckily, her sister-in-law lived close by and had given birth six months before, so she had lots of stuff to lend Theresa. Of course, being the eldest of eight meant that Theresa was used to looking after babies.

They adopted their second daughter, Siobhan, through the official channels. Theresa made her second name Mary Rose, the biological mother's name.

Theresa loved being a mum. After waiting so long for children, she poured her whole life into caring for her daughters. When they started school, she even worked as a dinner lady to ensure that her holidays coincided with the school breaks.